|

Edited on Tue Jan-26-10 01:33 AM by OnyxCollie

for a class I had last semester. It was theft on a grand scale. War is a Racket. Well, its a racket, all right. A few profit- and the many pay. But there is a way to stop it. You cant end it by disarmament conferences. You cant eliminate it by peace parlays at Geneva. Well-meaning but impractical groups cant wipe it out by resolutions. It can be smashed effectively only by taking the profit out of war.

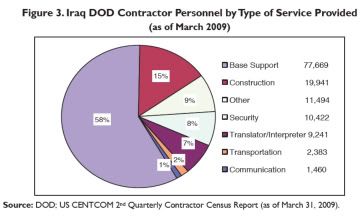

-Brigadier General Smedley D. Butler(1) IntroductionWar is, and always has been, a costly venture for nations to undertake. Whether it be a strained military, the depleted financial resources of the state, or the lives of hapless civilians caught in the crossfire, the toll of war will invariably be high. The decision to go to war must be a prudent one, and care must be taken to ensure efficiency in operations, with oversight to prevent skyrocketing costs as a result of waste and fraud. This essay will examine the use of defense contractors in Iraq, determine if federal funds are being misused (through waste, fraud, or abuse), and create a public policy to address the problem. Sources for this essay will include the Congressional Budget Office, the Congressional Research Service, the Government Accountability Office, and the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction. Determining the ProblemContractors have assisted the U.S. military since the Revolutionary War.(2) They support the military by providing goods and services the military can not or chooses not to provide. These services typically reside at both ends of the spectrum; they are either mundane duties or highly specialized tasks. In general, contractors provide transportation, engineering and construction, maintenance, base operations, and medical care (although this is now done primarily by military personnel).(3) Additionally, contractors now provide security for diplomatic envoys, high-value equipment, and areas of critical importance.(4) There are some restrictions as to what duties contractors may perform. These duties, determined to be inherently governmental, may only be performed by government personnel.(5) Such duties are regulated under the authority of the Federal Activities Inventory Reform Act and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to be so intimately related to the public interest that they must be performed by government personnel. Similarly, the Department of Defense (DOD) classifies some military actions as core or military essential.(6) Contractor work in Iraq is primarily in two areas -base support and construction- comprising approximately 77,669 personnel (58% of contractors) and 19,941 personnel (15% of contractors), respectively.(7) ![]()  (8) Contractors may be used in lieu of military personnel when circumstances restrict the number of troops in an area. Force caps are limits on troop capacity due to law, executive direction, or agreements with host countries or other allies.(9) Contractors are not included in the number of troops present. Contractor levels in Iraq numbered 132,610, with 141,300 military personnel present as of March 2009.(10) The DOD, which includes subcontractor totals in its data, estimates the number to be as high as 190,000.(11) The ratio of contractors to military personnel is 1 to 1.(12) Of those 132,610 contractors, 36,000 were U.S. citizens, 36,000 were local nationals, and 60,000 were third-country nationals.(13) In preparation for the Iraq War, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld objected to the recommendations that a half-million troops be sent to Iraq.(14) Central Command (CENTCOM) chief of war plans Colonel Mike Fitzgerald explained, We got told that it was old think, too big, wasnt innovative, and to readdress the planning using a different set of assumptions.(15) Believing such a large number of military personnel would lack the speed and agility needed to counter new challenges, and encouraged by improvements in military capabilities, Secretary Rumsfeld requested General Tommy Franks draw up battle plans for 160,000 soldiers.(16) This overconfidence would later prove costly once the security situation became detrimental. Postwar planning for Iraq, originally under the auspices of the Department of State (DOS), was turned over to the DOD at the recommendation of Secretary Rumsfeld.(17) Secretary of State Colin Powell agreed: State does not have the personnel, the capacity, or the size to deal with an immediate postwar situation in a foreign country thats eight thousand miles away from here.(18) On January 20, 2003, President Bush issued National Security Presidential Directive 24, which created the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Affairs (ORHA), the new office in the DOD for managing postwar Iraq.(19) The decision to remove postwar planning from the National Security Council (NSC) in the DOS and turn it over to the DOD was viewed with hostility. You dont need to worry about the nuts and bolts of basic reconstruction, NSC Director Frank Miller remembers two Defense officials saying. Its now an operation. Thereafter, Miller said, it was you guys stay out, we dont need your help. (20)

One month after the invasion of Iraq, President Bush signed P.L. 108-11.(21) Born from this law was the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund (IRRF), a $2.475 billion congressional appropriation to pay for reconstruction and humanitarian relief. Originally developed by the NSC, it was based on two premises- that Iraqs infrastructure would be unimpaired and that oil revenues would pay for reconstruction costs.(22)

Following the creation of the IRRF, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1483 (UNSCR 1483).(23) UNSCR 1483 formed the Development Fund for Iraq (DFI) which became a cache for Iraqs oil and gas revenues. These were to be deposited into the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, through which Iraqs temporary government, the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), could withdraw funds for reconstruction costs.(24)

Less than a month after the formation of the DFI, the CPA passed two regulations. The first regulation gave the head of the CPA, Ambassador L. Paul Bremer, total control of the DFI.(25) The second regulation created the Program Review Board (PRB).(26) The PRB managed the DFI in a transparent manner to meet Iraqs humanitarian needs, support the economic reconstruction, fund projects to repair Iraqs infrastructure, continue disarmament programs, and pay for the costs of the countrys civilian administration.(27)

Using its legal status as an international organization, the CPA was provided a loophole to dispense Iraq funds without succumbing to U.S. contracting regulations.(28) The CPA then developed its own procedures, which it failed to follow.(29) Additionally, CPAs Head of Contracting Activity (HCA) was put in charge of managing Iraqi ministry contracting until the ministries could be capable of the transparent use and management of Iraqi funds.(30)Money from the DFI was loaded onto pallets and transferred by plane:

The CPA relied on the DFI to fund the operations of Iraqs ministries and to pay for reconstruction projects. Held in a Federal Reserve Bank account in New York, DFI cash was flown to Baghdad in very large sums whenever the CPA requested. These shipmentsthe largest airborne transfer of currency in historyproved an enormous logistical challenge. A typical pallet of DFI cash had 640 bundles, with a thousand bills in each bundle. Each loaded pallet weighed about 1,500 pounds. The pallets were flown into Baghdads airport at night and were then driven to the Central Bank of Iraq for deposit.

The first emergency air-lift of money to Iraq was for $20 million, but the shipments rapidly grew in size. In December 2003, the CPA requested a $1.5 billion shipment, at the time the largest single payout of U.S. currency in Federal Reserve Bank history.16 But that record was soon broken when, in June 2004, more than $4 billion was flown to Iraq, just before the CPAs transfer of sovereignty to the Iraqi Interim Government.(31)

By November 2003, CPA had to scramble to meet growing reconstruction demands. Congress had appropriated $18.4 billion dollars to the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund (IRRF2)(32) and the CPA appointed Admiral Dave Nash to head the newly formed Program Management Office (PMO) to get the contracts in place.(33) Nashs solution was to outsource the contract management to private contractors.(34)

Nash requested 100 government personnel to staff the PMO, but was never able to get more than half.(35) As of January 2004, he had 8.(36) Those whom he did receive had less than stellar qualifications. Instead, he had to rely on private contractors to perform the inherently governmental duties. This was a cause for concern in Congress.

Noticing the failure to produce candidates for contracting positions, the DOD used its White House Liaison Office and a new federal law to fill positions at CPA.(37) The new law -Section 3161 in Title 5 of the United States Code- permitted federal hiring for temporary organizations without the standard requirements.(38) Despite this, the shortage of talent meant that the new law captured only the unqualified, and with the appearance of being politicized as well.

Lack of qualified personnel for contract oversight was a common theme.(39) Brigadier General Stephen Seay experienced similar problems when he became the CPAs HCA in February 2004.(40) Deluged by IRRF2 contracts, Seay struggled to keep up while a third of his 69 contracting positions remained vacant.(41) Retired Rear Admiral David Oliver had only four of his 39 positions filled during his five months as Director of CPAs OMB.(42) Olivers replacement, Rodney Bent, had a staff with no experience with budgets at all. I had a relatively young staff that was completely inexperienced and had no particular training either in the Middle East or on budget matters.(43)

The inexperienced, under qualified PMO staff rotated out of country constantly.(44) This was due to the belief that the U.S. stay in Iraq would be brief.(45) As a result, three month tours of duty were the norm. The high turnover rate meant that as soon as staff acquired on the job training, they were replaced.(46) If you couldnt get somebody for 90 days, youd take somebody for 60 days, said retired Lieutenant General Jeffery Oster.(47) Over the course of the CPAs fourteen-month existence, only seven people served the entire time.(48)

The lack of understanding of responsibilities by contracting officers resulted in insufficient monitoring of contractors.(49) Logistics Civilian Augmentation Contracts (LOGCAP), such as the one awarded to Halliburton/KBR in December 2001,(50) are cost-plus award fee contracts or fixed-price contracts.

Cost plus contracts allow the contractor to be reimbursed for reasonable, allowable, and allocable costs incurred to the extent prescribed in the contract. A cost-plus award fee contract provides financial incentives on the basis of performance. These contracts allow the government to evaluate a contractors performance according to specified criteria and to grant an award amount within designated parameters. Award fees can serve as a valuable tool to help control program risk and encourage excellence in contract performance. To reap the advantages that cost-plus contracts offer, the government must implement an effective award fee process.(51)

Award fees based on performance are an incentive to ensure quality work. However, failure of the contracting officers to require defense contractors to produce a definitized schedule of when work will be initiated and completed, and an absence of oversight of contractors progress on task orders, permits the possibility of long delays, substandard work, and wasted federal funds.(52)

Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement requires that undefinitized contract actions include a not-to-exceed cost and a definitization schedule. It also requires that the contract be definitized within 180 days or before 50 percent of the work to be performed is completed, whichever comes first.(53)

10 task orders, valued at $1,401,559,925, were scheduled to be definitized one year after they were required to be definitized.(54) A Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR) audit revealed contracting officers were not aware that Iraq task orders were required to be definitized, resulting in the loss of millions of taxpayer dollars.(55)

When contractors begin work before schedules are definitized, subsequent changes result in high costs.(56) In May 2004, Parsons was awarded a contract to build a maximum security prison.(57) Work on the task order, worth $73 million, was to begin in November. Due to the increase in hostilities, progress on the prison got off to a slow start. Almost two years later, Parsons made it known to the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers that completion of the prison could be expected in September 2008, three years late. The government terminated the contract. Two Iraqi contractors also failed to meet expectations. The government stopped work on the project completely. After three years and $40 million dollars, and all that was to show for the effort was a half-finished prison with poor construction. When the government turned it over to the Iraqis, they refused to take it. When SIGIR did an inspection of the incomplete facility, they found $1.2 million of material was missing.

The largest IRRF task order was awarded to KBR.(58) The task order required KBR to restore functionality to Iraqs natural gas liquid and liquified petroleum gas plants. The task order, comprising 20.3% of KBRs LOGCAP contract, was terminated due to cost overruns, schedule delays, and funding limitations.(59) At the time of termination, work had been nearly completed. The task order had been changed 35 times and $146.7 million worth of expenses had been incurred by KBR. KBRs expenses were disputed by the Defense Contract Audit Agency, which found half ($70 million) to be unsupported. The task order had an original not-to-exceed funding level of $5 million. The government settled with KBR on February 21, 2005, for a price of $133.5 million.(60)

Contractors are required to provide workers compensation insurance, known as Defense Base Act (DBA).(61) The cost of this insurance is covered by the cost-plus feature of the LOGCAP contract. An audit conducted by the Defense Contract Audit Agency of KBRs insurance premiums from 2003 to 2007 found that KBR paid $592 million.(62) An audit by the Army Audit Agency revealed that KBRs costs for DBA for fiscal year 2005 amounted to $284 million, yet KBRs insurance provider, American International Group (AIG) paid out only $73 million in claims.(63) The Army Audit Agency concluded the cost of DBA insurance substantially exceeded the losses experienced by the LOGCAP contractor.(64)

1 Butler, S. (1935). War is a Racket, p. 39

2 Congressional Budget Office. (2008). Contractors Support of U.S. Operations in Iraq, p. 12

3 Ibid, p. 6

4 Ibid, p. 12

5 Ibid, p. 18

6 Ibid

7 Schwartz, M. (2009). Department of Defense Contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan: Background and Analysis, p. 6

8 Ibid

9 Government Accountability Office. (2003). MILITARY OPERATIONS: Contractors Provide Vital Services to Deployed Forces but Are Not Adequately Addressed in DOD Plans, p. 6

10 Schwartz, M. (2009). Department of Defense Contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan: Background and Analysis, p. 5

11 Congressional Budget Office. (2008) Contractors Support of U.S. Operations in Iraq, p. 8

12 Ibid

13 Schwartz, M. (2009). Department of Defense Contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan: Background and Analysis, p. 7

14 Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction. (2009). Hard Lessons: The Iraq Reconstruction Experience, p. 35

15 Ibid, p. 34

16 Ibid, p. 35

17 Ibid, p. 33

18 Ibid

19 Ibid, pp. 33, 34

20 Ibid, p. 34

21 Ibid, p. 61

22 Ibid

23 Ibid, p. 80

24 Ibid

25 Ibid

26 Ibid

27 Ibid

28 Ibid, p. 81

29 Ibid

30 Ibid

31 Ibid, p. 88

32 Ibid, p. 103

33 Ibid, p. 105

34 Ibid, p. 106

35 Ibid, p. 107

36 Ibid, p. 108

37 Ibid, p. 83

38 Ibid

39 Government Accountability Office. (2004). MILITARY OPERATIONS: DODs Extensive Use of Logistics Support Contracts Requires Strengthened Oversight, p. 42

40 Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction. (2009). Hard Lessons: The Iraq Reconstruction Experience, p. 172

41 Ibid, p. 173

42 Ibid, p. 84

43 Ibid

44 Government Accountability Office. (2003). MILITARY OPERATIONS: Contractors Provide Vital Services to Deployed Forces but Are Not Adequately Addressed in DOD Plans, p. 30

45 Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction. (2009). Hard Lessons: The Iraq Reconstruction Experience, p. 82

46 Government Accountability Office. (2003). MILITARY OPERATIONS: Contractors Provide Vital Services to Deployed Forces but Are Not Adequately Addressed in DOD Plans, p. 29

47 Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction. (2009). Hard Lessons: The Iraq Reconstruction Experience, p. 83

48 Ibid

49 Ibid, p. 177

50 Government Accountability Office. (2004). MILITARY OPERATIONS: DODs Extensive Use of Logistics Support Contracts Requires Strengthened Oversight, p. 8

51 Ibid, p. 7

52 Ibid, p. 44

53 Ibid, p. 29

54 Ibid, p. 30

55 Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction. (2009). Hard Lessons: The Iraq Reconstruction Experience, p. 175

56 Government Accountability Office. (2004). MILITARY OPERATIONS: DODs Extensive Use of Logistics Support Contracts Requires Strengthened Oversight, p. 28

57 Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction. (2009). Hard Lessons: The Iraq Reconstruction Experience, p. 209

58 Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction. (2009). Cost, Outcome, and Oversight of Iraq Oil Contract with Kellog, Brown & Root Services, Inc. p. 21

59 Ibid, p. 20

60 Ibid, p. 24

61 Grasso, V. (2009). Defense Logistical Support Contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan: Issues for Congress, p. 9

62 Ibid

63 Ibid, p. 10

64 Ibid |