It's a condensed version of what I wanted to write. (It was a research methods class, so the focus was to be on the quantitative analysis more than the belief system topic.)

I tested whether fear would cause people (liberals, moderates, conservatives) to choose an authoritarian candidate and authoritarian measures.

For the first hypothesis (voting), the effects of the causal variables on the dependent

variables will be measured initially with crosstabulations and chi-square tests of independence

and later with independent sample

t-tests. For the second hypothesis (support for authoritarian

measures), the effects of the causal variable on the dependent variable will be measured by a

factorial ANOVA.

It will be predicted that in the first hypothesis, fear from the 9/11 terrorist attacks will

affect voters approval of and willingness to re-elect their congressional representatives, and will

increase the likelihood of voting for the Republican candidate. The Republican image of being

strong militarily protectors will persist, despite the failure to prevent the attacks from occurring.

It will be predicted that in the second hypothesis, fear from the 9/11 terrorist attacks will

affect respondents, in particular moderates and conservatives, to support laws to aid in terrorism

investigations and to sacrifice freedoms in support of those laws. Moderates will support laws

because they view things by group interest, i.e. as they have been attacked they will respond by

facilitating measures to prevent it from reoccurring, while conservatives will support laws

because of their authoritarian tendencies.

To test the first hypothesis, crosstabulations between the dependent variable,

congressional election vote (Democratic candidate or Republican candidate), and the

independent variable, re-elect representative or look around, yielded a response of 62% of those

choosing to re-elect their representative choosing to vote Republican, while those choosing to

look around was nearly evenly divided, with 52% choosing the Democratic candidate, chi-square

(1,

N = 1002) = 1.38E1,

p < .01. Adding a dichotomous control variable, concern over being

personally victimized by terrorism, produced significant results for both groups, with 59% of

those concerned about terrorism choosing to re-elect the Republican candidate and 57% of those

looking around choosing the Democratic candidate, chi-square (1,

N = 280) = 6.96,

p = .008. Of those not concerned about terrorism, 64% were willing to re-elect the Republican

candidate while 48% of those looking around would choose the Democratic candidate, chi-square

(1,

N = 451) = 6.07,

p = .014.

An independent sample

t-test was conducted between the dependent variable, re-elect

congressional representative, and the independent variable, trust (Most people can be trusted,

Cant be too careful). A significant result occurred,

t(834) = -4.58,

p < .01, with those

responding Cant be too careful having a higher score than Most people can be trusted.

Another independent sample t-test between the dependent variable, congressional election vote,

and the independent variable, trust, failed to produce significant results

t(745) = 1.37,

p = .171.

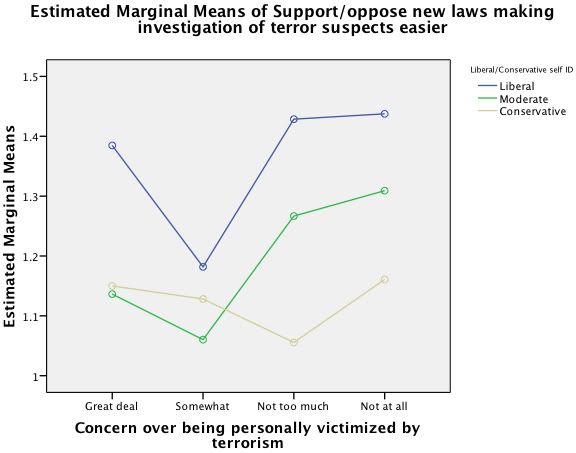

A factorial ANOVA to examine the effects of liberal conservative ideology and concern

over being personally victimized by terrorism on support for laws to make the FBIs

investigation of terrorism suspects easier was used to test the second hypothesis.

Figure 1.

![]()

Results indicated a significant effect for concern over terrorism,

F(3, 72) = 5.09,

p = .002, eta

= .17. Contrary to what was hypothesized, liberals who experienced a great deal of concern over

terrorism showed greater support for laws (

M = 1.38) than did moderates (

M = 1.14) or

conservatives (

M = 1.15). Liberals who were somewhat concerned showed a decrease in support

(

M = 1.18) but still more than moderates (

M = 1.06) or conservatives (

M = 1.13). However, when

the measures on concern for terrorism dropped to not too much and not at all, liberal support

for laws rose (

M = 1.43,

M = 1.44). Moderates followed a similar pattern (

M = 1.27, M = 1.31).

Conservative support dropped however, from somewhat concerned (M = 1.13) to not too

much (M = 1.06), before rising slightly on not at all (

M = 1.16). (See Figure 1.) A significant

effect was found for ideology, as well

F(2, 72) = 10.18,

p < .01, eta = .2. There was no

significant interaction between concern over terrorism and ideology

F(6, 72) = 1.8,

p = .097, eta

= .15.

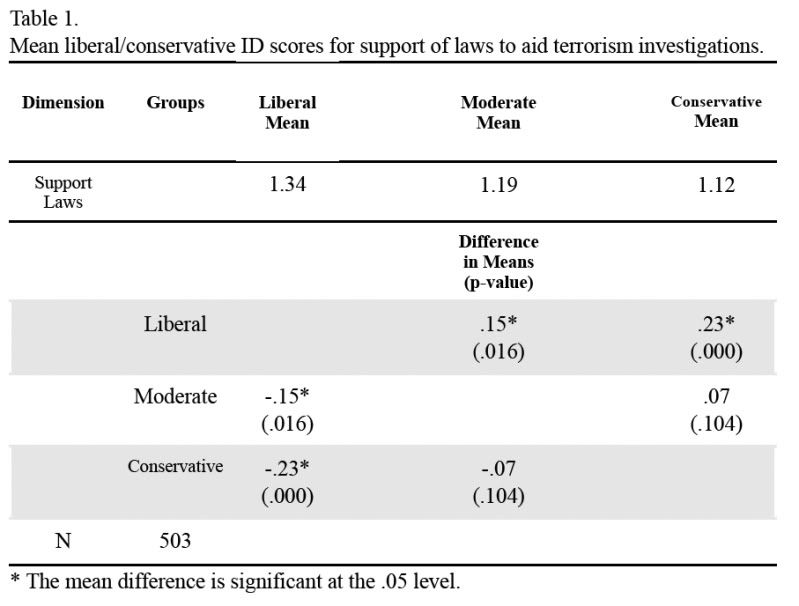

Since Levenes test of equality was violated, the Games-Howell post hoc test was used. (See Table 1.)

![]()

Hypothesis two was also tested with a factorial ANOVA to measure the effect of liberal

conservative ideology on the willingness to sacrifice freedoms in the investigation of terrorism

suspects. Results indicated no significant relationship between liberal conservative ideology on

the willingness to sacrifice freedoms

F(2, 76) = 1.79,

p = .168, eta = .09. No significant

relationship was detected between concern over being personally victimized by terrorism on the

willingness to sacrifice freedoms

F(1, 76) = .015,

p = .904, eta = 0. No significant relationship

was detected between liberal conservative ideology and concern over being personally

victimized by terrorism on the willingness to sacrifice freedoms

F(2, 76) = 1.70,

p = .183,

eta = .09. (See Table 2.)

![]()

((Full disclosure: Levene's Homogeneity of Variances wasn't met (the assumption that all groups are equal.) The result was insignificant, however. I tried to fix it, but I got confused using the Compute Variable in SPSS, so instead of the four point scale of concern I cheated and used a dichotomous yes/no variable for concern. It met Levene's assumption, didn't change much, and was still insignificant. It was a stupid question anyway, so fuck it.))

"Thus, closed belief systems reduce ambiguity-induced anxiety by satisfying the need to know."

"God works in mysterious ways." I hate that saying. It's what people say when they don't know what they're talking about, but want to rid themselves of the fear from anxiety. I hate it because it because once dogma starts, thinking stops.

It brought They Thought They Were Free to my mind:

http://dynamics.org/~altenber/LIBRARY/EXCERPTS/MAYER_MILTON/But Then It Was Too Late

What happened here was the gradual habituation of the people, little by little, to being governed by surprise; to receiving decisions deliberated in secret; to believing that the situation was so complicated that the government had to act on information which the people could not understand, or so dangerous that, even if he people could understand it, it could not be released because of national security. And their sense of identification with Hitler, their trust in him, made it easier to widen this gap and reassured those who would otherwise have worried about it.

This separation of government from people, this widening of the gap, took place so gradually and so insensibly, each step disguised (perhaps not even intentionally) as a temporary emergency measure or associated with true patriotic allegiance or with real social purposes. And all the crises and reforms (real reforms, too) so occupied the people that they did not see the slow motion underneath, of the whole process of government growing remoter and remoter.

You will understand me when I say that my Middle High German was my life. It was all I cared about. I was a scholar, a specialist. Then, suddenly, I was plunged into all the new activity, as the universe was drawn into the new situation; meetings, conferences, interviews, ceremonies, and, above all, papers to be filled out, reports, bibliographies, lists, questionnaires. And on top of that were the demands in the community, the things in which one had to, was expected to participate that had not been there or had not been important before. It was all rigmarole, of course, but it consumed all one's energies, coming on top of the work one really wanted to do. You can see how easy it was, then, not to think about fundamental things. One had no time.

Those, I said, are the words of my friend the baker. One had no time to think. There was so much going on. Your friend the baker was right, said my colleague. The dictatorship, and the whole process of its coming into being, was above all diverting. It provided an excuse not to think for people who did not want to think anyway. I do not speak of your little men, your baker and so on; I speak of my colleagues and myself, learned men, mind you. Most of us did not want to think about fundamental things and never had. There was no need to. Nazism gave us some dreadful, fundamental things to think about we were decent people and kept us so busy with continuous changes and crises and so fascinated, yes, fascinated, by the machinations of the national enemies, without and within, that we had no time to think about these dreadful things that were growing, little by little, all around us. Unconsciously, I suppose, we were grateful. Who wants to think?