http://www.theoildrum.com/node/6842Analyzing the current energy consumption of a city alone can lead to conclusions that urban areas, particularly dense urban areas, are relatively efficient, largely because per-capita current energy consumption is lower than in dispersed urban or suburban arrangements. This is indeed often the case. But what is not measured as part of the energy impact of urban areas is the built space itself—the streets, pavement, buildings, utilities, tunnels, etc.—that are required to maintain such a dense arrangement of humans, nor does it take into account the energy used to manufacture, transport, and sell the array of consumption goods and services that urban residents purchase. Since urban areas exist for people, looking at the urban energy footprint from the point of view of its inhabitants’ impact can provide additional insight into the nature of urban energy use.

...

The test city for the model was Suzhou (Figure 1), a large city of 6 million population located west of Shanghai in Jiangsu province. Suzhou is a prosperous city with an economy dominated by heavy industry, which accounts for 80% of the city’s energy consumption. It is home to Shagang, the 7th largest steel producer in the world with an output in 2009 of 26 million tonnes, equivalent to 45% of total US production in that year.

Much of this steel, however, is not consumed by Suzhou residents, and thus this large industrial component falls out of the model; instead Suzhou steel consumption is captured in the infrastructure and building use of steel and in the steel used to make products consumed by the residents, such as automobiles and refrigerators. Similarly, Suzhou residents eat food that is in part not locally grown, but the energy used to produce and transport this food to Suzhou is included in the calculation. In this way, the model creates a picture of Suzhou energy consumption oriented towards the people who are responsible for its consumption, and excludes energy consumption of those goods and services produced in Suzhou and consumed elsewhere.

...

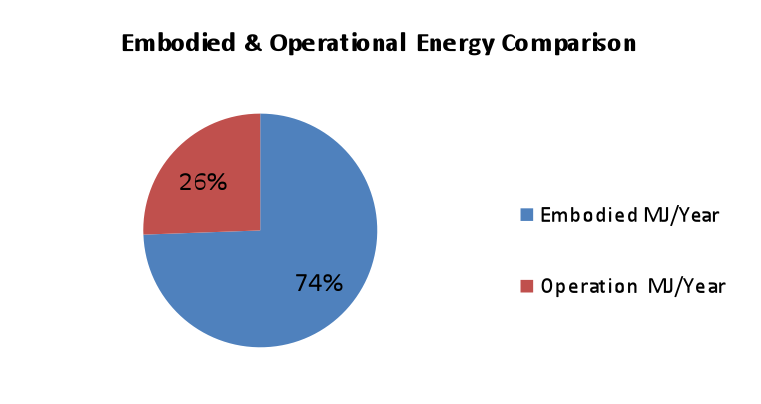

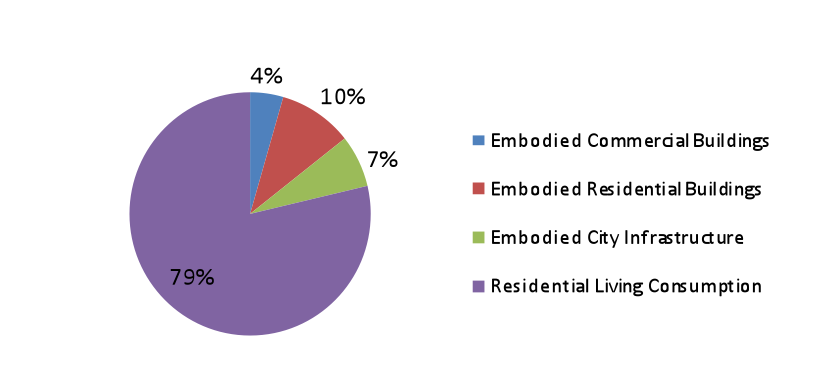

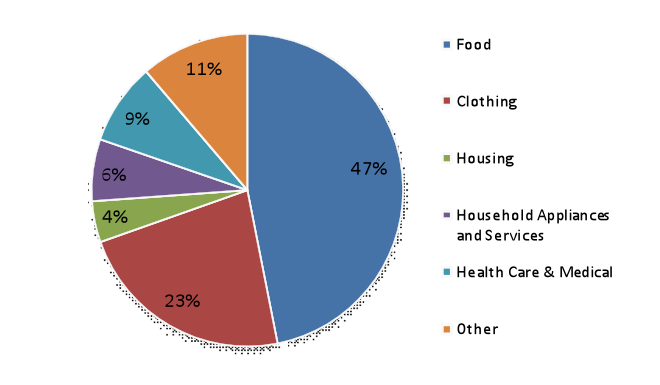

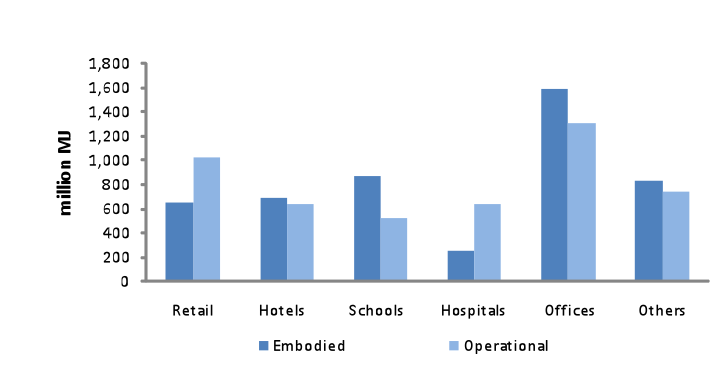

This approach to looking at the energy footprint of a city based on the impacts of the city’s inhabitants shows, in the case of Suzhou, that personal consumption of goods and services accounts for the largest (59%) contribution to energy footprint of the city, and this figure would likely remain above 50% even with inclusion of details omitted in this version of the model (mainly freight transport, water treatment, and embodied energy of vehicles). For a policy-maker, this suggests that supply-chain issues need to be considered, and of these supply chains, food appears to be dominant. Developing long-distance or international food supply chains as in the US would dramatically raise the energy demand of each resident and further decrease the food energy return on investment to less than the 0.5 it is today. It also makes apparent the impact of increasing wealth as rising household income is translated into higher consumption. In addition, this approach highlights the impact of building lifetime: design and code requirements that would raise the lifetime of buildings from the current 30 years to a US average of about 75 years (or a UK average of over 100 years) would further decrease the contribution of the embodied energy in buildings to even a lower proportion than found here. Similarly, it suggests that “green buildings” with low or net-zero operational energy may not be “green” at all if the embodied energy of the materials used in the building are considered in the calculation. This exercise also adds a different perspective to the impact of such popular programs such as encouraging CFL use or buying more fuel efficient cars: though important in their own right as a matter of waste reduction, the contribution to changing the overall energy picture is quite small.

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/6842