Robert Reich:

The Administration's biggest economic mistake so far was to badly underestimate last January how bad the employment situation would become by Fall. As a result, it low-balled the stimulus -- settling for a plan that, while avoiding even worse job losses, didn't go nearly far enough.

Obama has to return to Congress, seeking a larger stimulus.

Yes, I know. We're already in the gravitational pull of the midterm elections (look at the bizarre attention given to gubernatorial elections in New Jersey and Virginia, and even to a congressional election in the 23rd district of New York, as supposed harbingers of voter behavior a year from now!) so it will be even harder to round up the needed votes from Blue Dog Dems fretting over the deficit. And you can forget the Republicans.

And yes, I know: Only about half the current stimulus has been spent, so it will be awkward to make the case that we need a larger one.

But here's the problem. Everything else on the table -- a new jobs tax credit, more loans to small businesses, more help to troubled homeowners, another extension of unemployment insurance, another round of subsidies to first-time home buyers -- are small potatoes relative to the importance and likely effect of a larger stimulus. Some of these initiatives may do some good, but even combined they'll barely make a dent in the growing numbers of jobless Americans.

Meanwhile, the states are slicing their budgets, laying off workers, and ratcheting up taxes. That's because state tax revenues are falling off a cliff, and almost every state is barred by its constitution from running a deficit. That means the states are actively implementing an anti-stimulus plan.

moreNot sure why Reich believes small business lending is small potatoes.

At one point, before Obama took office, some were calling for a

$1 trillion package:

Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard University professor who was an adviser to Republican presidential candidate John McCain, and Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Prize winner who served in President Bill Clinton�s White House, are among those who say President- elect Barack Obama should push for a package of that size.

�They need a stimulus of $500-to-$600 billion a year for at least two years to counter what is going to be a collapse in consumption,� said Rogoff, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund.

<...>

�Congress should think in terms of $900 billion in 2009, with possibly more in 2010,� said James Galbraith, a self-styled liberal economics professor at the University of Texas in Austin who has talked with the Obama transition team about the issue. �I may be higher than they are at this point,� he said, �but things are evolving.�

Got that: from $500 -$600 billion for a year or two to $900 billion.

Krugman:

October 5, 2009, 10:04 am

I read the

Ryan Lizza piece on Larry Summers with a great sense of relief. It turns out that in talking to Ryan, I managed to say almost nothing worth quoting � which is, in these circumstances, very much the goal. (If I have something controversial to say, I�ll say it in the column or this blog, thank you.)

For me, the really interesting passage was this one:

The most important question facing Obama that day was how large the stimulus should be. Since the election, as the economy continued to worsen, the consensus among economists kept rising. A hundred-billion-dollar stimulus had seemed prudent earlier in the year. Congress now appeared receptive to something on the order of five hundred billion. Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel laureate, was calling for a trillion. Romer had run simulations of the effects of stimulus packages of varying sizes: six hundred billion dollars, eight hundred billion dollars, and $1.2 trillion. The best estimate for the output gap was some two trillion dollars over 2009 and 2010. Because of the multiplier effect, filling that gap didn�t require two trillion dollars of government spending, but Romer�s analysis, deeply informed by her work on the Depression, suggested that the package should probably be more than $1.2 trillion. The memo to Obama, however, detailed only two packages: a five-hundred-and-fifty-billion-dollar stimulus and an eight-hundred-and-ninety-billion-dollar stimulus. Summers did not include Romer�s $1.2-trillion projection. The memo argued that the stimulus should not be used to fill the entire output gap; rather, it was �an insurance package against catastrophic failure.� At the meeting, according to one participant, �there was no serious discussion to going above a trillion dollars.�

So Christy Romer�s math looked similar to mine: even given what we knew last December, the straight economics said that we should have a stimulus much bigger than the Obama administration�s initial proposal. And given what happened to that proposal in the Senate � we actually ended up with only about $600 billion of actual stimulus � what we eventually got was half of what seemed appropriate in December. And the actual news on the economy since then has been worse than was expected back then, so that the stimulus now looks way short of what we need.

Maybe that was all that could have been done, politically. But it does not sound, from the Lizza article, as if either the economic team or the political team thought much about the risks of finding themselves where we are now � with the economy still failing to deliver job growth despite the stimulus � even though those risks were completely

apparent at the time.

More

Krugman:

The

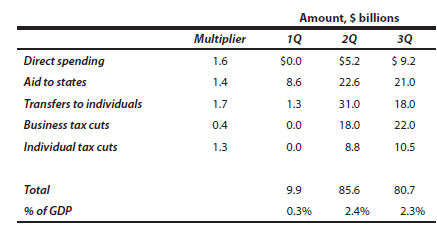

basic economic logic says that the stimulus should aim to close the output gap. And it�s obviously not remotely large enough to be doing that right now. Nor will it come close in the future. Here�s a useful table from EPI on the stimulus so far:

Economic Policy Institute

The key point from this table is that while most of the stimulus has yet to be spent, the

rate of spending as a percentage of GDP is already fairly high (take that,

Richard Posner), close to the maximum it will reach over the whole course of the plan. That means that we�ve already seen much if not most of the impact of the stimulus on growth.

A few caveats apply � mainly, some of the indirect effects will still mount over time. For example, the ARRA has probably saved as many schoolteachers� jobs as it�s going to � but the indirect effect of those jobs saved on, say, employment at the stores where the teachers buy their groceries hasn�t been fully felt yet. That�s why Christy Romer says that the ARRA�s effect won�t peak until the middle of next year.

Still, we�ve gotten the big boost, and it�s clearly far short of what we really need.

And yes, we can afford more.

The stimulus package was $787 billion. About a

third of that has been awarded. Obama is planning to divert

$317 billion from TARP to small business loans. Wouldn't that put the total economic stimulus at more than $1 trillion?

With all the numbers being thrown around and the calls for more stimulus, how much is enough? And, as Krugman suggests, how much more can we afford?