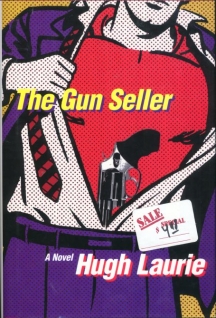

|

It's his only one so far, but it's a flat out hilarious take on the Ludlum/Forsythe thriller formula. Here's an excerpt from Chapter 1. Imagine that you have to break someone's arm.

Right or left, doesn't matter. The point is that you have to break it, because if you don't...well, that doesn't matter either. Let's just say bad things will happen if you don't.

Now, my question goes like this: do you break the arm quickly -- snap, whoops, sorry, here let me help you with that improvised splint -- or do you drag the whole business out for a good eight minutes, every now and then increasing the pressure in the tiniest of increments, until the pain becomes pink and green and hot and cold and altogether howlingly unbearable?

Well exactly. Of course. The right thing to do, the only thing to do, is to get it over with as quickly as possible. Break the arm, ply the brandy, be a good citizen. There can be no other answer.

Unless.

Unless unless unless.

What if you were to hate the person on the other end of the arm? I mean really, really hate them.

This was a thing I now had to consider.

I say now, meaning then, meaning the moment I am describing; the moment fractionally, oh so bloody fractionally, before my wrist reached the back of my neck and my left humerus broke into at least two, very possibly more, floppily joined-together pieces.

The arm we've been discussing, you see, is mine. It's not an abstract, philosopher's arm. The bone, the skin, the hairs, the small white scar on the point of the elbow, won from the corner of a storage heater at Gateshill Primary School -- they all belong to me. And now is the moment when I must consider the possibility that the man standing behind me, gripping my wrist and driving it up my spine with an almost sexual degree of care, hates me. I mean, really, really hates me.

He is taking for ever.

His name was Rayner. First name unknown. By me, at any rate, and therefore, presumably, by you too.

I suppose someone, somewhere, must have known his first name -- must have baptised him with it, called him down to breakfast with it, taught him how to spell it -- and someone else must have shouted it across a bar with an offer of a drink, or murmured it during sex, or written it in a box on a life insurance application form. I know they must have done all these things. Just hard to picture, that's all.

Rayner, I estimated, was ten years older than me. Which was fine. Nothing wrong with that. I have good, warm, non-arm-breaking relationships with plenty of people who are ten years older than me. People who are ten years older than me are, by and large, admirable. But Rayner was also three inches taller than me, four stones heavier, and at least eight however-you-measure-violence units more violent. He was uglier than a car park, with a big, hairless skull that dipped and bulged like a balloon full of spanners, and his flattened, fighter's nose, apparently drawn on his face by someone using their left hand, or perhaps even their left foot, spread out in a meandering, lopsided delta under the rough slab of his forehead.

And God Almighty, what a forehead. Bricks, knives, bottles and reasoned arguments had, in their time, bounced harmlessly off this massive frontal plane, leaving only the feeblest indentations between its deep, widely-spaced pores. They were, I think, the deepest and most widely-spaced pores I have ever seen in human skin, so that I found myself thinking back to the council putting-green in Dalbeattie, at the end of the long, dry summer of '76.

Moving now to the side elevation, we find that Rayner's ears had, long ago, been bitten off and spat back on to the side of his head, because the left one was definitely upside down, or inside out, or something that made you stare at it for a long time before thinking 'oh, it's an ear'.

And on top of all this, in case you hadn't got the message, Rayner wore a black leather jacket over a black polo-neck.

But of course you would have got the message. Rayner could have swathed himself in shimmering silk and put an orchid behind each ear, and nervous passers-by would still have paid him money first and wondered afterwards whether they had owed him any.  |