A culture is really just a set of ideas used by people to deal with changes in their environment and solve whatever problems arise from those changes. In that context, technology, ethics, religion, logic, and art are just tools in the toolbox that is our culture. The more tools you have, the more options you have when something happens like, for example, global warming, nuclear proliferation, a meteor strike, or the career of David Hasselhoff.

There is a common misconception that a single work of art can provide a clear and easily recognizable connection to it's cultural utility. That is far from the case. In fact, it could be argued that the works with the greatest utility exhibit their greatest worth only in the minds of the people thinking about them when those thoughts arise.

Here's an example:

The Nike swoosh is universally recognized as - the Nike swoosh. No matter what you think about it, good or bad, right or wrong, your thought is always directed specifically at the product represented by that logo to the exclusion of everything else. That is its function. It is designed to be identified with a single thing (the thing that makes Nike money) and nothing else. If it is working at its best, you will never think about anything else but Nike. It's function and it's impact on the viewer is clear, simple, to the point, and culturally barren.

The vast overwhelming number of images seen by the public are generated by corporations to perform that same function. They are designed to focus attention and reflection on the object that will make those corporations money. There is, for want of a better term, no feedback loop. All reflection is directed one way, toward the logo and what it stands for. Art works the other way.

This is a painting by Rene' Magritte designed to reveal that feedback loop:

The caption below the image reads, "This is not a pipe." It is also the title of the work. Well, of course it's not a pipe, it's a painting. But we recognize the image as that of a pipe, and we call it a pipe, so why is it not a pipe if that's what we call it...? It's like standing between two mirrors staring into a sort of infinite regression, trying to decide whether the goddamn thing is a pipe or not. The painting sets up a contradiction that refuses to answer the question that is quickly embraced by the corporate logo. It makes you think. A lot. About a goddamn pipe.

Now today you may decide it's just a painting of a pipe. Maybe sometime somebody will need to know what a pipe is and somebody else will be able to point to that painting and say, "there's one." Who knows, in a different state of mind you may decide it actually

is a pipe. It's possible, we do it in movies all the time. It's called the suspension of disbelief. That feedback loop, and the self reflection it facilitates, is where the utility of art can be found. It's use is not in the work itself, but in what we are able to make of it. The feedback loop that is created by all of the arts serves to create possible circumstances in our minds that may or may not ever come to pass. It also creates the potential for responses to those circumstances. To put it in scientific terms, if you want to test a hypothesis, push it to the limits of its testability. In the end, art is just cultural R&D.

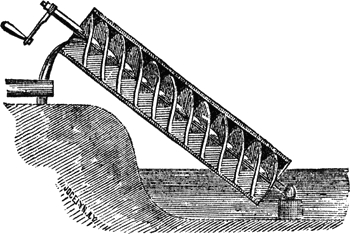

So if art is the addition of tools in our cultural tool box that gives us the potential for change, it would be safe to say some tools are better than others. When is the last time you needed one of these?

These, on the other hand, have been around a long time and will continue to be of use for a long time to come:

The egg slicer slices eggs. That's about it. Archimedes screw just keeps showing up all over the place all the time. The idea of the screw has a great deal more cultural utility than the idea of an egg slicer. Those are, of course, just examples to make a point. The egg slicer is a series of "knives" and the tool known as a knife will be around a long time as well. But the contrast between Archimedes screw, a principle with great potential for a variety of uses, and the egg slicer, the application of a tool for an extremely limited number of uses, highlights the difference between great art and corporate logos. One offers great potential, the other reduces it.

Basically a meme is an idea within a culture. Cultures develop along an evolutionary model, and the DNA of cultures are ideas. The utility of art (which are ideas) has been well illuminated by the science of Memetics. A meme is just a bit of cultural DNA. If in the process of evolution, a culture is able to frequently find a use for an idea, it keeps it in its DNA. If an idea is of little use, it is disposed of in the process of cultural evolution. Thus, a persistently useful meme has cultural utility. And a work of art that stays around for a long time is also a meme with cultural utility. But it only works if you use it.

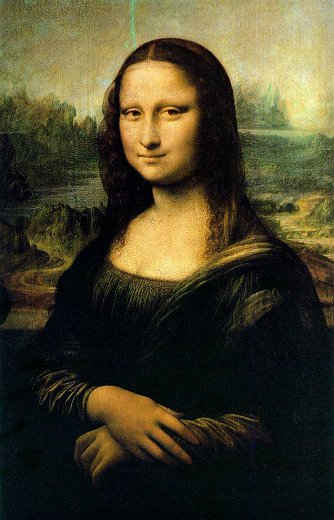

So with that in mind, let's set the Mona Lisa next to Mr. Gibson's movie and see how they fare.

This is a still from the movie:

I realize that this will be an uneven comparison since I can't make the entire movie play in this post, but bear with me. The film was touted by its producer, Mr. Gibson, as an accurate portrayal of the story of the trial, scourging, and Crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Thus, he has already admitted that there will be little real investigation of why it happened, or what the event actually means. He guarantees no feedback loop right off the bat. What he has done is to make clear to people that he is going to tell them exactly what they want to hear. He then proceeds to make the depiction of the events appear to be visually accurate, while simultaneously creating inaccuracies that compound the one way focus on the object itself to the exclusion any real self reflection. For example, the punishment that Christ endures at the hands of the Romans is well in excess of what any normal person could endure and survive long before he got to the hill at Calvary. But it affords Mr. Gibson the opportunity to apply liberal doses of violence and blood to generate tremendous empathy for the character of the Christ, emotions that preclude any critical analysis of that character. And that's just one example,

here here are a few more. Watching this movie is a one way street from the viewer to the object being viewed, with very few stops along the way.

Now, here is the Mona Lisa:

People for centuries have been confounded by her inscrutable smile. Who is she? Why is she smiling? What does her smile mean? Was she just one person, or a combination of the features of multiple sitters? How am I, as the viewer, to respond to the gaze directed out of the canvas at me? There is a relationship between the viewer and the artwork that is absent from the above mentioned film and its viewers. There is a feedback loop. In addition, the innaccuracies in the rendering of the face facilitate that feedback loop.

Now, there are no absolutes here. It could be that he cultural utility of the Mona Lisa is nearing it's end and that smile will become of increasingly little use as the years go on, although the value of the painting as a historical document will endure for much longer. And it is entirely possible that there are those who can create a viable feedback loop from Mr. Gibson's movie and actually learn something from it. But there won't be many. The Mona Lisa was designed to prompt questions, while Mr. Gibson's movie was designed to ask no meaningful questions and provide a single answer: Christ died for your eternal salvation, you owe Christ, and the church works for him. If Nike could just figure out how to get its logo in there, it will be a match made in heaven.