IN the days when Ashikaga was Shogun there served under him a knight of good family, Kato Sayemon, of whom he was especially fond. Things went well with Sayemon. He lived in what might almost be called a palace. Money he possessed in plenty. He had a charming wife who had borne him a son, and, according to old custom, he had many others who lived as wives within his mansion. There was no war in the land.

Sayemon found no trouble in his household. Peace and contentment reigned. He enjoyed life accordingly, by feasting and so forth. 'Oh that such a life could last!' thought he; but fate decreed otherwise.

One evening, when Sayemon was strolling about in his lovely garden, watching the fireflies and listening to singing insects and piping toads, of which he was extremely fond, he happened to pass his wife's room and to look up.

There he saw his dear wife and his favourite concubine playing chess ('go,' in Japanese). What struck him most was that they appeared perfectly happy and contented in each other's society. While Sayemon looked, however, their hair seemed to rear up from behind in the shapes of snakes which fought desperately. This filled him with fear.

Sayemon, in amazement, stealthily approached in order to see better; but he found the vision just the same. His wife and the other lady, when moving their men, smiled at each other, showing every sign of great courtesy; nevertheless, there remained the indistinct outlines of their hair assuming the forms of fighting snakes. Hitherto Sayemon had thought of them as almost sisters to each other, and so outwardly had they in fact appeared; but, now that he had seen the mysterious sign of the snakes, he knew that they hated each other more than could be understood by a man.

He became uneasy in his mind. Until then his life had been rendered doubly happy because he thought his home was peaceful; but now, he reflected, hatred and malice must be rampant in the house. Sayemon felt as if he were a rudderless boat, being drawn towards a cataract, from which no means of escape seemed possible.

He spent a sleepless night in meditation, during which he decided that to run away would be the safest course in the end. Peace was all that he craved for. To obtain it, he would devote himself to religious work for the rest of his life.

Next morning Kato Sayemon was nowhere to be found. There was consternation in the household. Men were dispatched here, there, and everywhere; but Sayemon could not be found. On the fifth or sixth day after the disappearance his wife reduced the establishment, but continued herself, with her little son Ishidomaro, to live in the house. Even the Shogun Ashikaga was greatly disconcerted at Sayemon's disappearance. No news of him came, and time passed on until a year had gone, and then another, when Sayemon's wife resolved to take Ishidomaro, aged five, and go in search.

For five weary years they wandered about, this mother and son, making inquiries everywhere; but not the slightest clue could they get, until at last one day they were staying at a village in Kishu, where they met an old man who told them that a year before he had seen Kato Sayemon at the temple of Koya San. 'Sure,' he said, 'I knew him, for I was once a palanquin-bearer for the Shogun, and often and often saw Sayemon San. I cannot say if he is at the temple; but he was a priest there a year ago.'

For Ishidomaro and his mother there was but little sleep that night. They were in a fever of excitement. Ishidomaro was now eleven years of age, and was most anxious to have his father at home; both mother and son, happy after their long years of searching, eagerly looked forward to the morrow.

Unfortunately, according to ancient regulations, Koya San temple and mountain were only for men. No woman was allowed to ascend to worship the image of Buddha on this mountain. Thus Ishidomaro's mother had to remain in the village while he went in quest of his father.

At daybreak he started, full of hope, and telling his mother not to fear. 'I will bring back father this very evening,' said he; 'and how happy we shall all be! Farewell for the time being, and fear not for me!' So saying, Ishidomaro went off. 'True,' he said, 'I do not know my father by sight; but he has a black mole over his left eye, and so have I; besides, I feel that it is my father I am going to meet.' With that and such other thoughts in his mind the boy plodded upwards through the tall and gloomy forests, stopping here and there at some wayside shrine to pray for success.

Higher and higher Ishidomaro climbedKoya San is near 1100 feet in heightuntil he reached the outer gates of the temple, of which the true name is 'Kongobuji,' for 'Koya San' means only 'Koya Mountain.'

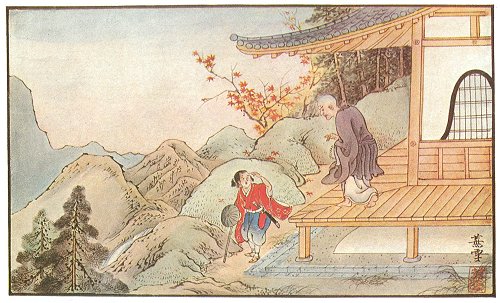

Arrived at the first priest's house, Ishidomaro espied an old man mumbling prayers.

'Please, sir,' said he, doffing his hat and bowing low, could you tell me if there is a priest here called Kato Sayemon? Greatly should I be obliged if you could direct me to him. He has only been a priest for five years. For all that time my dear mother and myself have been in search of him. He is my father, and we both love him much, and wish him to come back to us!'

'Ah, my lad, I feel sorry for you,' answered Sayemon (for it was indeed he). 'I know of no man called Kato Sayemon in these temples.' Delivering himself of this speech, Sayemon showed considerable emotion. He fully recognised that the boy he was addressing was his son, and he was under sore distress to deny him thus, and not to recognise and take him to his heart; but Sayemon had made up his mind that the rest of his life should be sacrificed for the sake of Buddha, and that all worldly things should be cast aside. Ishidomaro and his wife needed no money or food, but were well provided for; thus he need not trouble on those grounds. Sayemon determined to remain as he was, a poor monk, hidden in the monastery on Koya San. With a desperate effort he continued:

'I don't remember ever hearing of a Kato Sayemon's having been here, though, of course, I have heard of the Kato Sayemon who was the great friend of the Shogun Ashikaga.'

Ishidomaro was not at all satisfied with this answer. He felt somehow or other that he was in the presence of his father. Moreover, the priest had a black mole over his left eye, and he, Ishidomaro, had one exactly the same.

'Sir,' said he, again addressing the priest, 'my mother has always particularly drawn my attention to the mole over my left eye, saying, "My son, your father has such a mark over his left eye, the exact counterpart now, remember this, for when you go forth to seek him this will be a sure sign to you." You, sir, have the exact mark that I have. I know and feel that you are my father!'

With that, tears came into the eyes of Ishidomaro, and, outstretching his arms, he cried, 'Father, father, let me embrace you!'

Sayemon trembled all over with emotion; but haughtily held up his head and, recovering himself, said:

'My lad, there are many men and many boys who have moles over their left eyebrows, and even over their right. I am not your father. You must go elsewhere to seek him.'

At this moment the chief priest came and called Sayemon to the evening services, which were held in the main temple. Thus it was that Sayemon preferred to devote his life to Buddha, and (as Mr. Matsuzaki tells me) to emulate Buddha, rather than return to the ways of the world or to his family, or even to recognize his one and only son!

My sympathies are with Ishidomaro, of whom, as of his poor mother, we are told nothing further. To end in Mr. Matsuzaki's words:

'What became of Ishidomaro and his mother is not known; but it is told to this day that Kato Sayemon passed the rest of his life in peace and purity, entirely sacrificing his body and soul to Buddha, and did these things without any person to mourn over him, but in perfect contentment.'

In the third book of Sir Edwin Arnold's Light of Asia are the following verses, which were addressed to Buddha, when he was a Prince, by the winds:

We are the voices of the wandering wind;

Wander thou too, O Prince, thy rest to find;

Leave love for love of lovers, for woe's sake

Quit state for sorrow, and deliverance make.

So sigh we, passing oer the silver strings,

To thee who knowst not yet of earthly things;

So say we; mocking, as we pass away,

Those lovely shadows wherewith thou dost play.

No one, I feel sure, will fail to agree with me that Sayemon appears as a weak, selfish, and unheroic personagenot as a hero, much less as a Buddha.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj14.htm