THERE is a mountain in the province of Idsumi called Oki-yama (or Oji Yam a); it is connected with the Mumaru-Yama mountains. I will not vouch that I am accurate in spelling either. Suffice it to say that the story was told to me by Fukuga Sei, and translated by Mr. Ando, the Japanese translator of our Consulate at Kobe. Both of these give the mountain's name as Okiyama, and say that on the top of it from time immemorial there has been a shrine dedicated to Fudo-myo-o (Achala, in Sanskrit, which means 'immovable,' and is the god always represented as surrounded by fire and sitting uncomplainingly on as an example to others; he carries a sword in one hand, and a rope in the other, as a warning that punishment awaits those who are unable to overcome with honour the painful struggles of life).

Well, at the top of Oki-yama (high or big mountain) is this very old temple to Fudo, and many are the pilgrimages which are made there annually. The mountain itself is covered with forest, and there are some remarkable cryptomerias, camphor and pine trees.

Many years ago, in the days of which I speak, there were only a few priests living up at this temple. Among them was a middle-aged man, half-priest, half-caretaker, called Yenoki. For twenty years had Yenoki lived at the temple; yet during that time he had never cast eyes on the figure of Fudo, over which he was partly set to guard; it was kept shut in a shrine and never seen by any one but the head priest. One day Yenoki's curiosity got the better of him. Early in the morning the door of the shrine was not quite closed. Yenoki looked in, but saw nothing. On turning to the light again, he found that he had lost the use of the eye that had looked: he was stone-blind in the right eye.

Feeling that the divine punishment served him well, and that the gods must be angry, he set about purifying himself, and fasted for one hundred days. Yenoki was mistaken in his way of devotion and repentance, and did not pacify the gods; on the contrary, they turned him into a tengu (long-nosed devil who dwells in mountains, and is the great teacher of jujitsu).

But Yenoki continued to call himself a priest'Ichigan Hoshi,' meaning the one-eyed priestfor a year, and then died; and it is said that his spirit passed into an enormous cryptomeria tree on the east side of the mountain. After that, when sailors passed the Chinu Sea (Osaka Bay), if there was a storm they used to pray to the one-eyed priest for help, and if a light was seen on the top of Oki-yama they had a sure sign that, no matter how rough the sea, their ship would not be lost.

It may be said, in fact, that after the death of the one-eyed priest more importance was attached to his spirit and to the tree into which it had taken refuge than to the temple itself. The tree was called the Lodging of the One-eyed Priest, and no one dared approach itnot even the woodcutters who were familiar with the mountains. It was a source of awe and an object of reverence.

At the foot of Oki-yama was a lonely village, separated from others by fully two ri (five miles), and there were only one hundred and thirty houses in it.

Every year the villagers used to celebrate the 'Bon' by engaging, after it was over, in the dance called 'Bon Odori.' Like most other things in Japan, the 'Bon' and the 'Bon Odori' were in extreme contrast. The Bon' was a ceremony arranged for the spirits of the dead, who are supposed to return to earth for three days annually, to visit their family shrinessomething like our All Saints' Day, and in any case quite a serious religious performance. The 'Bon Odori' is a dance which varies considerably in different provinces. It is confined mostly to villagesfor one cannot count the pretty geisha dances in Kyoto which are practically copies of it. It is a dance of boys and girls, one may say, and continues nearly all night on the village green. For the three or four nights that it lasts, opportunities for flirtations of the most violent kind are plentiful. There are no chaperons (so to speak), and (to put it vulgarly) every one 'goes on the bust'! Hitherto-virtuous maidens spend the night out as impromptu sweethearts; and, in the village of which this story is told, not only is it they who let themselves go, but even young brides also.

So it came to pass that the village at the foot of Oki-yama mountainaway so far from other villageswas a bad one morally. There was no restriction to what a girl might do or what she might not do during the nights of the 'Bon Odori.' Things went from bad to worse until, at the time of which I write, anarchy reigned during the festive days. At last it came to pass that after a particularly festive 'Bon,' on a beautiful moonlight night in August, the well-beloved and charming daughter of Kurahashi Yozaemon, O Kimi, aged eighteen years, who had promised her lover Kurosuke that she would meet him secretly that evening, was on her way to do so. After passing the last house in her mountain village she came to a thick copse, and standing at the edge of it was a man whom O Kimi at first took to be her lover. On approaching she found that it was not Kurosuke, but a very handsome youth of twenty-three years. He did not speak to her; in fact, he kept a little away. If she advanced, he receded. So handsome was the youth, O Kimi felt that she loved him. 'Oh how my heart beats for him!' said she. 'After all, why should I not give up Kurosuke? He is not good-looking like this man, whom I love already before I have even spoken to him. I hate Kurosuke, now that I see this man.'

As she said this she saw the figure smiling and beckoning, and, being a wicked girl, loose in her morals, she followed him and was seen no more. Her family were much exercised in their minds. A week passed, and O Kimi San did not return.

A few days later Tamae, the sixteen-year-old daughter of Kinsaku, who was secretly in love with the son of the village Headman, was awaiting him in the temple grounds, standing the while by the stone figure of Jizodo (Sanskrit, Kshitigarbha, Patron of Women and Children). Suddenly there stood near Tamae a handsome youth of twenty-three years, as in the case of O Kimi; she was greatly struck by the youth's beauty, so much so that when he took her by the hand and led her off she made no effort to resist, and she also disappeared.

And thus it was that nine girls of amorous nature disappeared from this small village. Everywhere for thirty miles round people talked and wondered, and said unkind things.

In Oki-yama village itself the elder people said: Yes: it must be that our children's immodesty since the 'Bon Odori' has angered Yenoki San: perhaps it is he himself who appears in the form of this handsome youth and carries off our daughters.'

Nearly all agreed in a few days that they owed their losses to the Spirit of the Yenoki Tree; and as soon as this notion had taken root the whole of the villagers locked and barred themselves in their houses both day and night. Their farms became neglected; wood was not being cut on the mountain; business was at a standstill. The rumour of this state of affairs spread, and the Lord of Kishiwada, becoming uneasy, summoned Sonobé Hayama, the most celebrated swordsman in that part of Japan.

'Sonobé, you are the bravest man I know of, and the best fighter. It is for you to go and inspect the tree where lodges the spirit of Yenoki. You must use your own discretion. I cannot advise as to what it is best that you should do. I leave it to you to dispose of the mystery of the disappearances of the nine girls.'

'My lord,' said Sonobé, 'my life is at your lordship's call. I shall either clear the mystery or die.'

After this interview with his master Sonobé went home. He put himself through a course of cleansing. He fasted and bathed for a week, and then repaired to Oki-yama.

This was in the month of October, when to me things always look their best. Sonobé ascended the mountain, and went first to the temple, which he reached at three o'clock in the afternoon, after a hard climb. Here he said prayers before the god Fudo for fully half an hour. Then he set out to cross the short valley which led up to the Oki-yama mountain, and to the tree which held the spirit of the one-eyed priest, Yenoki.

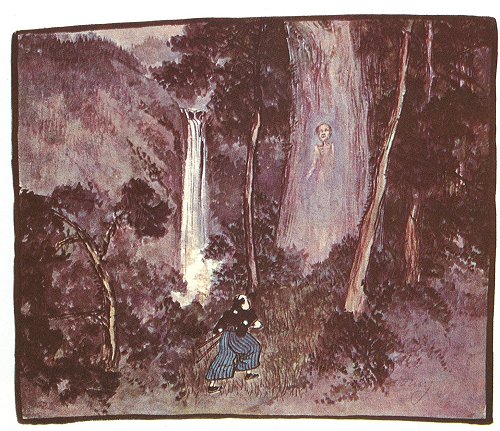

It was a long and steep climb, with no paths, for the mountain was avoided as much as possible by even the most adventurous of woodcutters, none of whom ever dreamed of going up as far as the Yenoki tree. Sonobé was in good training and a bold warrior. The woods were dense; there was a chilling damp, which came from the spray of a high waterfall. The solitude was intense, and once or twice Sonobé put his hand on the hilt of his sword, thinking that he heard some one following in the gloom; but there was no one, and by five o'clock Sonobé had reached the tree and addressed it thus:

'Oh, honourable and aged tree, that has braved centuries of storm, thou hast become the home of Yenoki's spirit. In truth there is much honour in having so stately a lodging, and therefore he cannot have been so bad a man. I have come from the Lord of Kishiwada to upbraid him, however, and to ask what means it that Yenoki's spirit should appear as a handsome youth for the purpose of robbing poor people of their daughters. This must not continue; else you, as the lodging of Yenoki's spirit, will be cut down, so that it may escape to another part of the country.'

At that moment a warm wind blew on the face of Sonobé, and dark clouds appeared overhead, rendering the forest dark; rain began to fall, and the rumblings of earthquake were heard.

Suddenly the figure of an old priest appeared in ghostly form, wrinkled and thin, transparent and clammy, nerve-shattering; but Sonobé had no fear.

'You have been sent by the Lord of Kishiwada,' said the ghost. 'I admire your courage for coming. So cowardly and sinful are most men, they fear to come near where my spirit has taken refuge. I can assure you that I do no evil to the good. So bad had morals become in the village, it was time to give a lesson. The villagers customs defied the gods. It is true that I, hoping to improve these people and make them godly, assumed the form of a youth, and carried away nine of the worst of them. They are quite well. They deeply regret their sins, and will reform their village. Every day I have given them lectures. You will find them on the "Mino toge," or second summit of this mountain, tied to trees. Go there and release them, and afterwards tell the Lord of Kishiwada what the spirit of Yenoki, the one-eyed priest, has done, and that it is always ready to help him to improve his people. Farewell!'

No sooner had the last word been spoken than the spirit vanished. Sonobé, who felt somewhat dazed by what the spirit had said, started off nevertheless to the 'Mino toge'; and there, sure enough, were the nine girls, tied each to a tree, as the spirit had said. He cut their bonds, gave them a lecture, took them back to the village, and reported to the Lord of Kishiwada.

Since then the people have feared more than ever the spirit of the one-eyed priest. They have become completely reformed, an example to the surrounding villages. The nine houses or families whose daughters behaved so badly contribute annually the rice eaten by the priests of Fudo-myo-o Temple. It is spoken of as 'the nine-families rice of Oki.'

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj43.htm