SOME twelve miles south of Shodo shima (Shodo island) is the large island of Nao or Naoshima, on the western side of the enchanting Inland Sea, which it has been my good fortune to cruise over at will, helped, instead of being hindered, by the Japanese Government, in consequence of the kindness of Sir Ernest Satow. Naoshima has but few inhabitants, not, I think, more than from sixty to a hundred; in the time of our story, about the year 1156, there were only two,Sobei and his good wife O Yone. These lived alone at a beautiful little bay, where they had built a fishing-hut, and cultivated some three thousand tsubo of land, with the produce of which and an unlimited supply of fish they were perfectly happy, untroubled by the quarrels of the day, which were then particularly serious, it being the Hogen period, which, lasting from 1156 to 1160, took its name from what was known as the Hogen rebellion or (to put it correctly) revolution. It was during this exciting period that the ex-Emperor Shutoku (life, 1124-1141), who was suspected of leading the rebellion, was for safety banished by those in power to the island of Naoshima.

Stranded, marooned in little else than the clothes he stood in, he was in an unenviable plight. As far as he knew, the island was desolate. After his marooners had left him he strolled on the beach, wondering what next he should do. Should he take his life, or should he struggle to retain it? While pondering these questions night overcame Shutoku before he had thought of making a shelter, and he sat, in consequence, contemplating the past and listening to the sad waves.

Next morning, as the sun rose above the horizon, the ex-Emperor began to move. He had resolved to live. He had not gone far along the beach when he found marks of feet upon the sand, and shortly afterwards, from across a little rocky promontory, he saw smoke ascending in the still air. Lightened in heart, the ex-Emperor stepped out, and after some twenty minutes of stiff climbing came down into the bay where stood the hut of Sobei and his wife. Marching boldly up, he told them who he was, and how he had been marooned and exiled, and asked them many questions.

'Sir,' said Sobei, 'my wife and I are very humble people. We live in peace, for there are none to disturb us here, and we are passing through our lives very happily. To our humble fare you are truly welcome. Our cottage is small; but you shall have its shelter while we build another and a better for you, and at all times we shall be your servants.'

The ex-Emperor was pleased to hear these words of friendship, and became one of the family. He helped to build a lodge for himself. He helped the old couple in their fishing and agriculture, and became deeply attached to them.

n the autumn he fell ill, and was nursed through a dangerous fever, his medicines being made by O Yone from leaves, seaweeds, and other natural products of the island; and towards the spring he began to recover. In his convalescence the ex-Emperor went out one day to sit by the sea and admire the scenery, and became so absorbed in a flock of seagulls that were following a school of sardines that he failed to notice what was going on around him. When he looked up suddenly it was to find himself surrounded by no less than fourteen Samurai in armour.

As soon as they noticed that the ex-Emperor had seen them, one the eldest, a grey-haired and benevolent-looking old man, stepped up to him, and, bowing, said:

'Oh, my beloved Sovereign, at last I have found you! My name is Furuzuka Iga, and regretfully I am obliged to tell you that I am sent by the Mikado to secure your head. He fears while you live, even in banishment, for the peace of the country. Please enable me to take your head as speedily and as painlessly as possible. It is my misfortune to have to do it.'

The ex-Emperor seemed in no way surprised at this speech. Without a word, he arranged himself and stretched his neck to receive the blow from Iga's sword.

Iga, touched by his manly conduct, began to weep, and exclaimed:

'Oh, what a brave sovereign! What a samurai! How I grieve to be his executioner!' But his duty was plain: so he nerved himself and struck off the ex-Emperor's head with a single blow.

As soon as the head fell upon the sand the other samurai came up and respectfully placed the head in a silken bag and awaited orders from their chief.

'My friends,' said Furuzuka Iga, 'go back to the boat and take the head of Shutoku to the Emperor. Tell him that his orders have been carried out, and that he need have no future fear. Go without me, for I remain here to weep over the deed which I have had to do.'

The Samurai were astonished; but they departed, and Iga gave way to grief.

Soon it came to pass that Sobei and his wife went to look for the ex-Emperor, for his absence had been long. They knew the spot where he loved to sit and gaze at the beautiful scenery. Thus it was that they found Iga weeping.

'What is this?' they cried. 'What means this blood upon the sand? Who, sir, may you be, and where is our guest?'

Iga explained that he was an envoy from the Mikado, and that it had been his painful duty to kill the ex-Emperor.

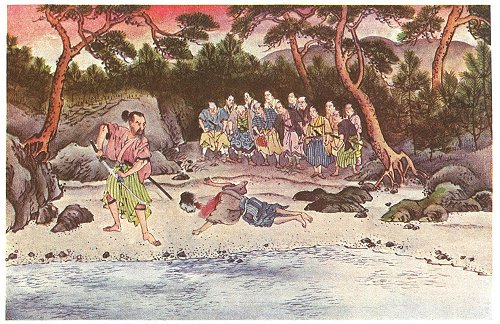

The fury of Sobei and his wife knew no bounds. Instinctively they decided that they must both die after avenging the ex-Emperor by killing Iga. They proceeded to attack him with their knivesSobei in front and his wife from behind.

Iga avoided them by his proficiency in jujitsu. In two seconds he had both of them by the wrists, and then said:

'Good people,for I know you to be such,listen to my story. The ex-Emperor who has been in exile on this island for nearly a year, and whom you have befriended and prevented from perishing from starvation and exposure, is not the real ex-Emperor, but my own son Furuzuka Taro!'

Sobei and his wife looked at him in bewilderment, and asked for an explanation.

'Listen, and I will tell you,' said Furuzuka Iga. 'As the result of the revolution in the Imperial Household, ex-Emperor Shutoku was taken for the enemy of the reigning Emperor, and was sentenced to exile on this island, which was supposed to be uninhabited, and is so for all but yourselves. The ex-Emperor must have died had you not been here to support him, and, though I am attached to the Imperial Court, I did not like one who had been my sovereign so to perish. It was my duty to bring the ex-Emperor here and maroon him. I marooned instead my own son, who was very much like him, and was glad to take the ex-Emperor's place. Unfortunately, the Mikado's mind became uneasy during the winter, fearing that so long as the ex-Emperor remained alive there might be further trouble, and I was again sent to Naoshima Island, this time to bring back the ex-Emperor's head. You know now what I have had to do.

Was ever a father called upon to carry out so terrible a commission? Pity me; be not angered. You have lost your friend, and I my son; but the ex-Emperor still lives; moreover, he knows of my loyalty to him, and will be here shortly in secret and in disguise. That is why I have remained, and that is the whole of the story I have to tell; and both of you must know how deeply grateful I feel towards you both in your great kindness to my son Taro.'

The poor samurai bowed to the ground, and the old couple, too simple to know what to do, remained silent, with tears of sorrow and of sympathy streaming down their faces.

For fully half an hour nothing was said. They remained weeping on the blood-stained beach, waiting for the tide to rise and wash away the marks; and they might have been longer had it not been that suddenly they heard the sweet strains of the biwa (a musical instrument of four strings, a lute) Then Iga arose and, drying his eyes, said, 'Here, my friends, comes the real ex-Emperor, though in disguise. He never goes anywhere without his lute, and he has signs and signals with me by certain airs he plays. He is asking now if it is safe to come forward, and if I give no answer it is safe. Listen, and see him approach!'

Sobei and his wife had never listened to such soft and bewitching music before, and, hearts full of sorrow, they sat listening. Nearer and nearer the music came, until they saw coming along the beach a man in poor clothes, whom they might almost have mistaken for their dead friend, so like was he to him.

When he came nearer, Iga went up and bowed, and then led the stranger to the fisherman and his wife, whom he made known, telling the ex-Emperor what kindness they had shown his son Taro. The ex-Emperor was pleased, and said that he was deeply grateful and considered them as part of that faithful body who had worked to save his life. Just then a ship was seen to round the point of the bay. It was the ship in which Iga had arrived, the ship which had borne away his son's head. The ex-Emperor, followed by Iga, Sobei, and his wife, kneeled on the sand near the bloody stain, and prayed long for the peace of the spirit of Taro.

Next day the ex-Emperor announced his intention of remaining for the rest of his life on the island of Naoshima with Sobei and O Yone. Iga was taken to the mainland by Sobei, and found his way back to the capital.

The ex-Emperor, attended by the faithful old couple, lived for a year on the island. His time was passed in playing on the biwa and in praying for the spirit of Taro. At the end of the year he died from mournfulness. Sobei and his wife devoted all their spare time to building a small shrine to his memory. It is said to be standing to this day.

In the third year of Ninnan the famous but eccentric priest and poet, Saigyo, who was related to the Imperial family, spent seventeen days on the island, praying night and day. During this time he sat on the favorite rock of Taro and the ex-Emperor. The rock is still known as 'Saigyo iwa' (Saigyo's Rock).

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj27.htm