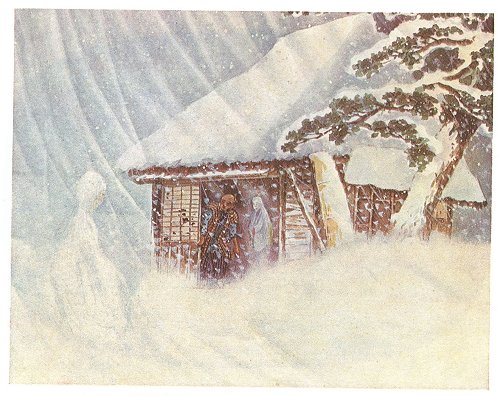

PERHAPS there are not many, even in Japan, who have heard of the 'Yuki Onna' (Snow Ghost). It is little spoken of except in the higher mountains, which are continually snowclad in the winter. Those who have read Lafcadio Hearn's books will remember a story of the Yuki Onna, made much of on account of its beautiful telling, but in reality not better than the following.

Up in the northern province of Echigo, opposite Sado Island on the Japan Sea, snow falls heavily. Sometimes there is as much as twenty feet of it on the ground, and many are the people who have been buried in the snows and never found until the spring. Not many years ago three companies of soldiers, with the exception of three or four men, were destroyed in Aowomori; and it was many weeks before they were dug out, dead of course.

Mysterious disappearances naturally give rise to fancies in a fanciful people, and from time immemorial the Snow Ghost has been one with the people of the North; while those of the South say that those of the North take so much saké that they see snow-covered trees as women.

Be that as it may, I must explain what a farmer called Kyuzaemon saw.

In the village of Hoi, which consisted only of eleven houses, very poor ones at that, lived Kyuzaemon. He was poor, and doubly unfortunate in having lost both his son and his wife. He led a lonely life.

In the afternoon of the 19th of January of the third year of Tem-pothat is, 1833a tremendous snowstorm came on. Kyuzaemon closed the shutters, and made himself as comfortable as he could. Towards eleven o'clock at night he was awakened by a rapping at his door; it was a peculiar rap, and came at regular intervals. Kyuzaemon sat up in bed, looked towards the door, and did not know what to think of this. The rapping came again, and with it the gentle voice of a girl. Thinking that it might be one of his neighbour's children wanting help, Kyuzaemon jumped out of bed; but when he got to the door he feared to open it. Voice and rapping coming again just as he reached it, he sprang back with a cry: 'Who are you? What do you want?'

'Open the door! Open the door!' came the voice from outside.

'Open the door! Is that likely until I know who you are and what you are doing out so late and on such a night?'

'But you must let me in. How can I proceed farther in this deep snow? I do not ask for food, but only for shelter.'

'I am very sorry; but I have no quilts or bedding. I can't possibly let you stay in my house.'

'I don't want quilts or bedding,only shelter,' pleaded the voice. 'I can't let you in, anyway,' shouted Kyuzaemon. 'It is too late and against the rules and the law.'

Saying which, Kyuzaemon rebarred his door with a strong piece of wood, never once having ventured to open a crack in the shutters to see who his visitor might be. As he turned towards his bed, with a shudder he beheld the figure of a woman standing beside it, clad in white, with her hair down her back. She had not the appearance of a ghost; her face was pretty, and she seemed to be about twenty-five years of age. Kyuzaemon, taken by surprise and very much alarmed, called out:

'Who and what are you, and how did you get in? Where did you leave your geta? (Wooden Shoes).'

I can come in anywhere when I choose,' said the figure, 'and I am the woman you would not let in. I require no geta; for I whirl along over the snow, sometimes even flying through the air. I am on my way to visit the next village; but the wind is against me. That is why I wanted you to let me rest here. If you will do so I shall start as soon as the wind goes down; in any case I shall be gone by the morning.'

'I should not so much mind letting you rest if you were an ordinary woman. I should, in fact, be glad; but I fear spirits greatly, as my forefathers have done,' said Kyuzaemon.

'Be not afraid. You have a butsudan? (spiritual alter)' asked the figure.

'Yes: I have a butsudan,' said Kyuzaemon; 'but what can you want to do with that?' 'You say you are afraid of the spirits, of the effect that I may have upon you. I wish to pay my respects to your ancestors' tablets and assure their spirits that no ill shall befall you through me. Will you open and light the butsudan?'

'Yes,' said Kyuzaemon, with fear and trembling: 'I will open the butsudan, and light the lamp. Please pray for me as well, for I am an unfortunate and unlucky man; but you must tell me in return who and what spirit you are.'

'You want to know much; but I will tell you,' said the spirit. 'I believe you are a good man. My name was Oyasu. I am the daughter of Yazaemon, who lives in the next village. My father, as perhaps you may have heard, is a farmer, and he adopted into his family, and as a husband for his daughter, Isaburo. Isaburo is a good man; but on the death of his wife, last year, he forsook his father-inlaw and went back to his old home. It is principally for that reason that I am about to seek and remonstrate with him now.'

'Am I to understand,' said Kyuzaemon, 'that the daughter who was married to Isaburo was the one who perished in the snow last year? If so, you must be the spirit of Oyasu or Isaburo's wife?'

'Yes: that is right,' said the spirit. 'I was Oyasu, the wife of Isaburo, who perished now a year ago in the great snowstorm, of which to-morrow will be the anniversary.'

Kyuzaemon, with trembling hands, lit the lamp in the little butsudan, mumbling 'Namu Amida Butsu; Namu Amida Butsu' with a fervour which he had never felt before. When this was done he saw the figure of the Yuki Onna (Snow Spirit) advance; but there was no sound of footsteps as she glided to the altar.

Kyuzaemon retired to bed, where he promptly fell asleep; but shortly afterwards he was disturbed by the voice of the woman bidding him farewell. Before he had time to sit up she disappeared, leaving no sign; the fire still burned in the butsudan.

Kyuzaemon got up at daybreak, and went to the next village to see Isaburo, whom he found living with his father-in-law, Yazaemon.

'Yes,' said Isaburo: 'it was wrong of me to leave my late wife's father when she died, and I am not surprised that on cold nights when it snows I have been visited continually by my wife's spirit as a reproof. Early this morning I saw her again, and I resolved to return. I have only been here two hours as it is.'

On comparing notes Kyuzaemon and Isaburo found that directly the spirit of Oyasu had left the house of Kyuzaemon she appeared to Isaburo, at about half-an-hour after midnight, and stayed with him until he had promised to return to her father's house and help him to live in his old age.

That is roughly my story of the Yuki Onna. All those who die by the snow and cold become spirits of snow, appearing when there is snow; just as the spirits of those who are drowned in the sea only appear in stormy seas.

Even to the present day, in the north, priests say prayers to appease the spirits of those who have died by snow, and to prevent them from haunting people who are connected with them.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj51.htm