IN the wild province of Yamato, or very near to its borders, is a beautiful mountain known as Yoshino yama. It is not only known for its abundance of cherry blossom in the spring, but it is also celebrated in relation to more than one bloody battle. In fact, Yoshino might be called the staging-place of historical battles. Many say, when in Yoshino, 'We are walking on history, because Yoshino itself is history.' Near Yoshino mountain lay another, known as Tsubosaka; and between them is the Valley of Shimizutani, in which is the Violet Well.

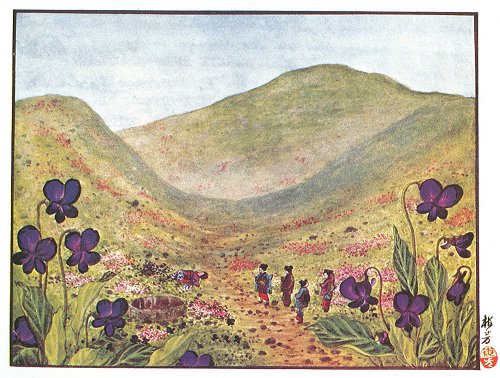

At the approach of spring in this tani the grass assumes a perfect emerald green, while moss grows luxuriantly over rocks and boulders. Towards the end of April great patches of deep-purple wild violets show up in the lower parts of the valley, while up the sides pink and scarlet azaleas grow in a manner which beggars description.

Some thirty years ago a beautiful girl of the age of seventeen, named Shingé, was wending her way up Shimizutani, accompanied by four servants. All were out for a picnic, and all, of course, were in search of wildflowers. O Shingé San was the daughter of a Daimyo who lived in the neighborhood. Every year she was in the habit of having this picnic, and coming to Shimizutani at the end of April to hunt for her favourite flower, the purple violet (sumire).

The five girls, carrying bamboo baskets, were eagerly collecting flowers, enjoying the occupation as only Japanese girls can. They raced in their rivalry to have the prettiest basketful. There not being so many purple violets as were wanted, O Shingé San said, 'Let us go to the northern end of the valley, where the Violet Well is.'

Naturally the girls assented, and off they all ran, each eager to be there first, laughing as they went.

O Shingé out ran the rest, and arrived before any of them; and, espying a huge bunch of her favourite flowers, of the deepest purple and very sweet in smell, she flung herself down, anxious to pick them before the others came. As she stretched out her delicate hand to grasp themoh, horror!a great mountain snake raised his head from beneath his shady retreat. So frightened was O Shingé San, she fainted away on the spot.

In the meanwhile the other girls had given up the race, thinking it would please their mistress to arrive first. They picked what they most fancied, chased butterflies, and arrived fully fifteen minutes after O Shingé San had fainted.

On seeing her thus laid out on the grass, a great fear filled them that she was dead, and their alarm increased when they saw a large green snake coiled near her head.

They screamed, as do most girls amid such circumstances; but one of them, Matsu, who did not lose her head so much as the others, threw her basket of flowers at the snake, which, not liking the bombardment, uncoiled himself and slid away, hoping to find a quieter place. Then all four girls bent over their mistress. They rubbed her hands and threw water on her face, but without effect. O Shines beautiful complexion became paler and paler, while her red lips assumed the purplish hue that is a sign of approaching death. The girls were heartbroken. Tears coursed down their faces. They did not know what to do, for they could not carry her. What a terrible state of affairs!

Just at that moment they heard a man's voice close behind them:

'Do not be so sad! I can restore the young lady to consciousness if you will allow me.'

They turned, and saw a remarkably handsome youth standing on the grass not ten feet away.

Without saying more, the young man approached the prostrate figure of O Shingé, and, taking her hand in his, felt her pulse. None of the servants liked to interfere in this breach of etiquette. He had not asked permission; but his manner was so gentle and sympathetic that they could say nothing.

The stranger examined O Shingé carefully, keeping silence. Having finished, he took out of his pocket a little case of medicine, and, putting some white powder from this into a paper, said:

'I am a doctor from a neighbouring village, and I have just been to see a patient at the end of the valley. By good fortune I returned this way, and am able to help you and save your mistress's life. Give her this medicine, while I hunt for and kill the snake.'

O Matsu San forced the medicine, along with a little water, into her mistress's mouth, and in a few minutes she began to recover.

Shortly after this the doctor returned, carrying the dead snake on a stick.

'Is this the snake you saw lying by your young mistress?' he asked.

'Yes, yes,' they cried: 'that is the horrible thing.'

'Then,' said the doctor, 'it is lucky I came, for it is very poisonous, and I fear your mistress would soon have died had I not arrived and been able to give her the medicine. Ah! I see that it is already doing the beautiful young lady good.'

On hearing the young man's voice O Shingé San sat up.

'Pray, sir, may I ask to whom I am indebted for bringing me thus back to life?' she asked.

The doctor did not answer, but in a proud and manly way contented himself by smiling, and bowing low and respectfully after the Japanese fashion; and departed as quietly and unassumingly as he had arrived, disappearing in the sleepy mist which always appears in the afternoons of spring time in the Shimizu Valley.

The four girls helped their mistress home; but indeed she wanted little assistance, for the medicine had done her much good, and she felt quite recovered. O Shingé's father and mother were very grateful for their daughter's recovery; but the name of the handsome young doctor remained a secret to all except the servant girl Matsu.

For four days O Shingé remained quite well; but on the fifth day, for some cause or another, she took to her bed, saying she was sick. She did not sleep, and did not wish to talk, but only to think, and think, and think. Neither father nor mother could make out what her illness was. There was no fever.

Doctors were sent for, one after another; but none of them could say what was the matter. All they saw was that she daily became weaker. Asano Zembei, Shingé's father, was heartbroken, and so was his wife. They had tried everything and failed to do the slightest good to poor O Shingé.

One day O Matsu San craved an interview with Asano Zembeiwho, by the by, was the head of all his family, a Daimyo and great grandee. Zembei was not accustomed to listen to servants' opinions; but, knowing that O Matsu was faithful to his daughter and loved her very nearly as much as he did himself, he consented to hear her, and O Matsu was ushered into his presence.

'Oh, master,' said the servant, 'if you will let me find a doctor for my young mistress, I can promise to find one who will cure her.'

'Where on earth will you find such a doctor? Have we not had all the best doctors in the province and some even from the capital? Where do you propose to look for one?'

O Matsu answered:

'Ah, master, my mistress is not suffering from an illness which can be cured by medicinesnot even if they be given by the quart. Nor are doctors of much use. There is, however, one that I know of who could cure her. My mistress's illness is of the heart. The doctor I know of can cure her. It is for love of him that her heart suffers; it has suffered so from the day when he saved her life from the snake-bite.'

Then O Matsu told particulars of the adventure at the picnic which had not been told before,for O Shingé had asked her servants to say as little as possible, fearing they would not be allowed to go to the Valley of the Violet Well again.

'What is the name of this doctor?' asked Asano Zembei, 'and who is he?'

'Sir,' answered O Matsu, 'he is Doctor Yoshisawa, a very handsome young man, of most courtly manners; but he is of low birth, being only of the eta.(The eta are the lowest people or caste in Japanskinners and killers of animals.)

Please think, master, of my young mistress's burning heart, full of love for the man who saved her lifeand no wonder, for he is very handsome and has the manners of a proud samurai. The only cure for your daughter, sir, is to be allowed to marry her lover.'

O Shingé's mother felt very sad when she heard this. She knew well (perhaps by experience) of the illnesses caused by love. She wept, and said to Zembei:

'I am quite with you in sorrow, my lord, at the terrible trouble that has come to us; but I cannot see my daughter die thus. Let us tell her we will make inquiries about the man she loves, and see if we can make him our son-in-law. In any case, it is the custom to make full inquiries, which will extend over some days; and in this time our daughter may recover somewhat and get strong enough to hear the news that we cannot accept her lover as our son-in-law.'

Zembei agreed to this, and O Matsu promised to say nothing to her mistress of the interview.

O Shingé San was told by her mother that her father, though he had not consented to the engagement, had promised to make inquiries about Yoshisawa.

O Shingé San took food and regained much strength on this news; and when she was strong enough, some ten days later, she was called into her father's presence, accompanied by her mother.

'My sweet daughter,' said Zembei, 'I have made careful inquiries about Dr. Yoshisawa, your lover. Deeply as it grieves me to say so, it is impossible that I, your father, the head of our whole family, can consent to your marriage with one of so low a family as Yoshisawa, who, in spite of his own goodness, has sprung from the eta. I must hear no more of it. Such a contract would be impossible for the Asano family.'

No one ventured to say a word to this. In Japan the head of a family's decision is final.

Poor O Shingé bowed to her father, and went to her own room, where she wept bitterly; O Matsu, the faithful servant, doing her best to console her.

Next morning, to the astonishment of the household, O Shingé San could nowhere be found. Search was made everywhere; even Dr. Yoshisawa joined in the search.

On the third day after the disappearance one of the searchers looked down the Violet Well, and saw poor O Shines floating body.

Two days later she was buried, and on that day Yoshisawa threw himself into the well.

The people say that even now, on wet, stormy nights, they see the ghost of O Shingé San floating over the well, while some declare that they hear the sound of a young man weeping in the Valley of Shimizutani.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj05.htm