In a novel approach, neurobiologists have tried to understand the central nervous system of a small round worm with 302 neurons but with nearly the same number of genes as humans. In this way, the activity of individual neurons and genes can be teased out.

By NICHOLAS WADE

Published: June 20, 2011

In an eighth-floor laboratory overlooking the East River, Cornelia I. Bargmann watches two colleagues manipulate a microscopic roundworm. They have trapped it in a tiny groove on a clear plastic chip, with just its nose sticking into a channel. Pheromones — signaling chemicals produced by other worms — are being pumped through the channel, and the researchers have genetically engineered two neurons in the worm’s head to glow bright green if a neuron responds.

These ingenious techniques for exploring a tiny animal’s behavior are the fruit of many years’ work by Dr. Bargmann’s and other labs. Despite the roundworm’s lowliness on the scale of intellectual achievement, the study of its nervous system offers one of the most promising approaches for understanding the human brain, since it uses much the same working parts but is around a million times less complex.

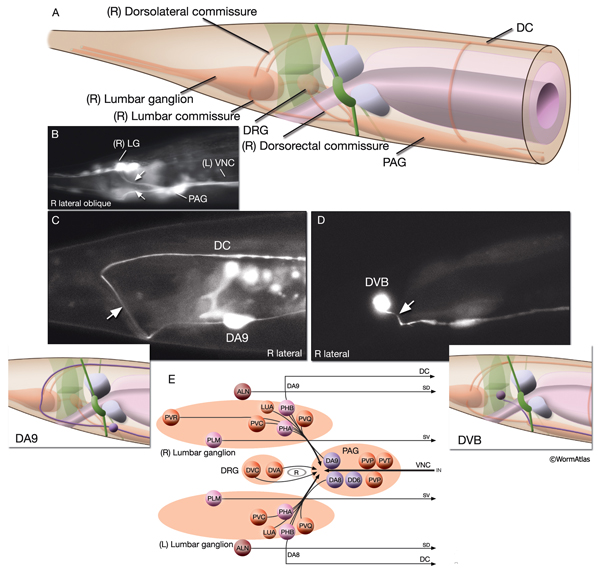

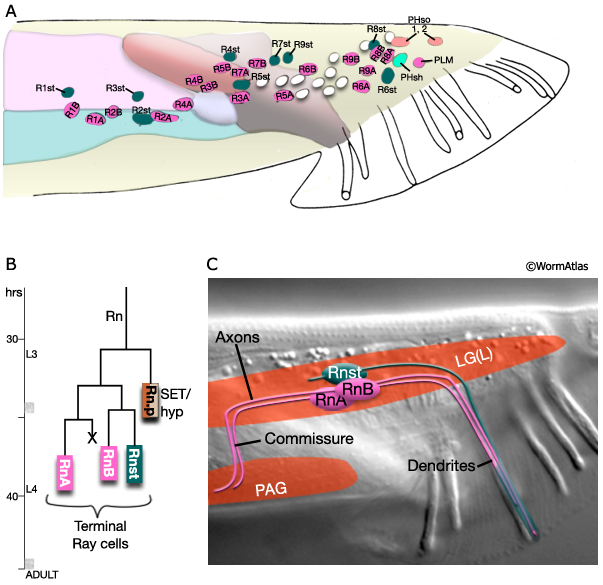

Caenorhabditis elegans, as the roundworm is properly known, is a tiny, transparent animal just a millimeter long. In nature, it feeds on the bacteria that thrive in rotting plants and animals. It is a favorite laboratory organism for several reasons, including the comparative simplicity of its brain, which has just 302 neurons and 8,000 synapses, or neuron-to-neuron connections.

The human brain, though vastly more complex than the worm’s, uses many of the same components, from neuropeptides to transmitters. So everything that can be learned about the worm’s nervous system is likely to help with the human system.

In Tiny Worm, Unlocking Secrets of the Brain