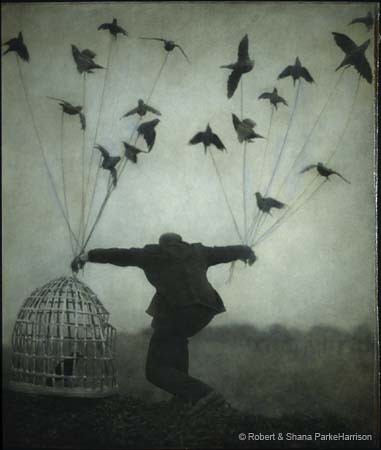

SPIRITUAL FLIGHT _______________

The Conference of the Birds

The Conference of the Birds (Persian: منطق الطیر, Mantiq at-Tayr, 1177) is a book of poems in Persian by Farid ud-Din Attar of approximately 4500 lines. The poem uses a journey by a group of 30 birds, led by a hoopoe as an allegory of a Sufi sheikh or master leading his pupils to enlightment.

Besides being one of the most beautiful examples of Persian poetry, this book relies on a clever word play between the words Simorgh a mysterious bird in Iranian mythology which is a symbol often found in sufi literature, and similar to the phoenix bird and "si morgh" meaning "thirty birds" in Persian.

In the 1970s, the poem was adapted into a play by Peter Brook and Jean-Claude Carrière (called The Conference of The Birds), which Brook took touring around the wilds of Africa before presenting two extremely successful productions to a Western audience, one in New York City at La MaMa, E.T.C. and one in Paris.<2>

The story recounts the longing of a group of birds who desire to know the great Simorgh, and who under the guidance of a leader bird start their journey toward the land of Simorgh. One by one, they drop out of the journey, each offering an excuse and unable to endure the journey. Each bird has a special significance, and a corresponding didactic fault. The guiding bird is the hoopoe, while the nightingale symbolizes the lover. The parrot is seeking the fountain of immortality, not god and the peacock symbolizes the "fallen soul" who is in alliance with Satan.

The birds must cross seven valleys in order to find the Simorgh: Aban (Flash), Ishq (Love), Marifat (Gnosis), Istighnah (Detachment), Tawheed (Unity of God), Hayrat (Bewilderment) and, finally, Fuqur and Fana (Selflessness and Oblivion in God). These represent the stations that a Sufi or any individual must pass through to realize the true nature of God.

Within the larger context of the story of the journey of the birds, Attar masterfully tells the reader many didactic short, sweet stories in captivating poetic style. Eventually only thirty birds remain as they finally arrive in the land of Simorgh all they see there are each other and the reflection of the thirty birds in a lake not the mythical Simorgh. It is the Sufi doctrine that God is not external or separate from the universe, rather is the totality of existence. The thirty birds seeking the Simorgh realise that Simorgh is nothing more than their transcendent totality. In fact the word "Simorgh" in Persian means thirty birds. The idea of God within is an idea intrinsic to most interpretations of Sufism dating back to the roots of Islam and can be found throughout the Qu'ran. As the birds realize the truth, they now reach the station of Baqa (Subsistence) which sits atop the Mountain Qaf.

A summary of the story:

http://oldpoetry.com/opoem/24929-Farid-al-Din-Attar-Conference-Of-The-Birdshttp://www.geocities.com/zeeshanhasan/birds.htmlThe text:

http://persian.packhum.org/persian/main?url=pf%3Ffile%3D02602030%26ct%3D0

This last section of the poem, in which the remaining thirty of the original thousand birds finally discover the Simorgh, depends on a pun; si means 'thirty', morgh means 'bird". So the si morgh finally meet the Simorgh.

The thirty birds read through the fateful page

And there discovered, stage by detailed stage,

Their lives, their actions, set out one by one -

All that their souls had ever been or done;

And this was bad enough, but as they read

They understood that it was they who'd led

The lovely Joseph into slavery -

Who had deprived him of his liberty

Deep in a well, then ignorantly sold

Their captive to a passing chief for gold.

(Can you not see that at each breath you sell

The Joseph you imprisoned in that well,

That he will be the king to whom you must

Naked and hungry bow down in the dust?)

The chastened spirits of these birds became

Like crumbled powder, and they shrank with shame.

Then, as by shame their spirits were refined

Of all the world's weight, they began to find

A new life flow towards them from that bright

Celestial and ever-living Light -

Their souls rose free of all they'd been before;

The past and all its actions were no more.

Their life came from that close, insistent sun

And in its vivid rays they shone as one.

There in the Simorgh's radiant face they saw

Themselves, the Simorgh of the world - with awe

They gazed, and dared at last to comprehend

They were the Simorgh and the journey's end.

They see the Simorgh - at themselves they stare,

And see a second Simorgh standing there;

They look at both and see the two are one,

That this is that, that this, the goal is won.

They ask (but inwardly; they make no sound)

The meaning of these mysteries that confound

Their puzzled ignorance - how is it true

That 'we' is not distinguished here from 'you'?

And silently their shining Lord replies:

'I am a mirror set before your eyes,

And all who come before my splendor see

Themselves, their own unique reality;

You came as thirty birds and therefore saw

These selfsame thirty birds, not less nor more;

If you had come as forty, fifty - here

An answering forty, fifty would appear;

Though you have struggled, wandered, traveled far,

It is yourselves you see and what you are.'

(Who sees the Lord? It is himself each sees;

What ant's sight could discern the Pleiades?

What anvil could be lifted by an ant?

Or could a fly subdue and elephant?)

'How much you thought you knew and saw; but you

Now know that all you trusted was untrue.

Though you traversed the Valley's depths and fought

With all the dangers that the journey brought,

They journey was in Me, the deeds were Mine -

You slept secure in Being's inmost shrine.

And since you came as thirty birds, you see

These thirty birds when you discover Me,

The Simorgh, Truth's last flawless jewel, the light

In which you will be lost to mortal sight,

Dispersed to nothingness until once more

You find in Me the selves you were before.'

Then, as they listened to the Simorgh's words,

A trembling dissolution filled the birds -

The substance of their being was undone,

And they were lost like shade before the sun;

Neither the pilgrims nor their guide remained.

The Simorgh ceased to speak, and silence reigned.

A hundred thousand centuries went by,

And then those birds, who were content to die,

To vanish in annihilation, saw

Their Selves had been restored to them once more,

That after Nothingness they had attained

Eternal Life, and self-hood was regained.

This Nothingness, this Life, are states no tongue

At any time has adequately sung -

Those who can speak still wander far away

From the dark truth they struggle to convey,

And by analogies they try to show

The forms men's partial knowledge cannot know.

No stranger followed them, or could unfold

The secrets they to one another told -

Alone at last, together they conferred;

Blindly they saw themselves and deaf they heard -

But who can speak of this? I know if I

Betrayed my knowledge I would surely die;

If it were lawful for me to relate

Such truths to those who have not reached this state,

Those gone before us would have made some sign;

But no sign comes, and silence must be mine.

Here eloquence can find no jewel but one,

That silence when the longed-for goal is won.

The greatest orator would here be made

In love with silence and forget his trade,

And I too cease: I have described the Way -

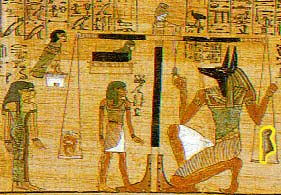

Now, you must act - there is no more to say. These words by the lead bird (the hoopoe) near the beginning of the poem reminded me of the ancient practice among the Egyptians where, in death, one comes to judgement and must weigh one's heart against that of a feather:

If this same feather had not floated down,

The world would not be filled with His renown -

It is a sign of Him, and in each heart

There lies this feather's hidden counterpart.

One of many wonderful scenes in ancient Egyptian art is The Judgment, sometimes called The Weighing of the Heart. It appears in the papyrus scrolls of The Egyptian Book of the Dead. The scene shows a deceased Egyptian named Ani being led to the chamber of his judgment. The god Anubis, the underworld guide, brings Ani before a huge scale. On one side of the scale, Anis heart is placed in a jar. On the other side of the scale is the feather of the goddess Maat. Observing this weighing of the heart are various other gods. Thoth (Hermes, to the Greeks) stands nearby with Anis Book of Life in his hands, ready to inscribe the outcome of this weighing. Horus, the god who was immaculately conceived by Isis to save the world from Egypts satan, waits to see if Anis heart is light enough for him to lead Ani out of the underworld through Osiris chamber and on up into the heavens. Isis and Nephthys stand behind Osiris, who is seated on his throne. All await the outcome. If ones heart were heavy with regret, unfinished Earth business, or the pull of selfish desires, then the ancient Egyptian -- in this case, Ani -- could not enter the heavens. A beastly creature would eat his heart, and he would have to return to Earth to get a new heart, one light enough to rise into heaven (presumably by reincarnating and living a better life than before).

___________________________________________________