GORDON PARKS, director of "The Learning Tree" and "Shaft," documentary & art photographer; 1912-2006

"He was stillborn -- no heartbeat, declared dead by the family doctor, and put aside for later burial. Another doctor in the delivery room had an idea, and immersed the newborn in ice-cold water. The shock caused his heart to start beating, and the baby was soon crying and healthy, and named for Dr Gordon, who had saved his life. In the more than ninety years of his life, Gordon Parks became internationally renowned as a photographer, filmmaker, poet, novelist, and composer.

He grew up poor in Fort Scott, Kansas, the youngest of 15 children. One of his early memories was hearing his all-black class told by their white schoolteacher, "You'll all wind up porters and maids." His mother died when Parks was 14, and he was sent to live with an older sister in Minneapolis, until her husband kicked him out. Between bouts of homelessness, he earned rent as a piano player in a bordello. He also worked as a busboy, a Civilian Conservation Corpsman, and as his teacher had predicted, as a porter and later waiter on the transcontinental North Coast Limited.

At 25, he bought a used camera for $7.50 and began working as a self-taught free-lance photographer"

"Parks, who had admired the Farm Security Administration photographs for some time, planned to spend his fellowship year as an apprentice photographer in Stryker's section and had received encouragement from the FSA Jack Delano when he was applying for the fellowship.4 But when he arrived in Washington, he recalled in 1983, Stryker resisted, expressing worries about the reaction of others--in the agency as well as in the city--to a black photographer. "When I went there," Parks said, "Roy didn't want to take me into the FSA, but the Rosenwald people were a part of that whole Rooseveltian thing. They insisted: 'Roy, you've got to do it.'" As Parks remembered it, Will Alexander--the vice-president of the Rosenwald Fund and the former head of the Farm Security Administration and thus Stryker's old boss--delivered the final nudge.5

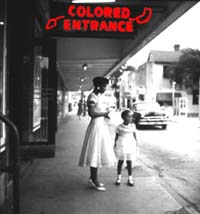

Parks's autobiography and interviews emphasize the importance of the education Stryker gave him.6 After asking Parks to leave his cameras in the office, Stryker sent the newly arrived photographer around Washington, instructing him to visit stores, restaurants, and theaters. When Parks was refused service, he became furious and returned to the office ready to "show the rest of the world what your great city of Washington, D.C. is really like," proposing to photograph scenes of injustice and portraits of bigots. In response, Stryker sent Parks to the file to study the work of Lange, Shahn, Evans, Delano, Rothstein, and others. Parks studied their photographs of gutted fields, dispossessed migrants, and the gaunt faces of people caught in the Depression. Although some might lay these tragedies to God, Parks wrote, "the research accompanying these stark photographs accused man himself--especially the lords of the land." As the effectiveness of photographing victims instead of perpetrators and the importance of the words that accompany photographs sank in, Parks concluded, "I began to get the point."7

One evening a few weeks later when he was alone in the office with Stryker, Parks said he was still seeking a way to expose intolerance with a camera. Stryker pointed out a charwoman at work in the building. "Go have a talk with her," he said, "See what she has to say about life and things." Parks complied, and later recalled his first conversation with Ella Watson:

She began to spill out her life's story. It was a pitiful one. She had struggled alone after her mother had died and her father had been killed by a lynch mob. She had gone through high school, married and become pregnant. Her husband was accidentally shot to death two days before their daughter was born. By the time the daughter was eighteen, she had given birth to two illegitimate children, dying two weeks after the second child's birth. What's more, the first child had been striken with paralysis a year before its mother died."

"Death was surely absent from his face two days before they killed him."

- Gordon Parks essay "The Death of Malcolm X" (Born Black, 1971)

Gordon Parks

Children, Frederick Douglass Housing Project,

Anacostia, Washington, D.C., 1942

Copyprint of gelatin silver print

Prints and Photographs Division

LC-USF34-013369-C (50)

Gordon Parks directing "The Learning Tree" in Kansas, 1968

Theatre Poster for 2000 re-release of "Shaft" (1971)

GORDON PARKS 1912-2006

SOURCES:

http://www.nndb.com/people/248/000027167/http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/fsahtml/fachap07.htmlhttp://www.culturevulture.net/Television/GordonParks.htmhttp://www.albany.edu/writers-inst/parksflm.htmlhttp://www.columbia.edu/cu/news/05/02/sundance.html